Genghis Khan’s Special Tool For Winning His Empire Wasn’t An Army

The power of spirituality in ruling a truly global empire

“The similarity and interchangeability of the words “Khan” and “kam,” or king and shaman in Steppe history, is a reflection of the near inseparability of religious and political power of that time.”

— Genghis Khan and the Quest For God, Jack Weatherford

What does it take to create an empire? While I’m sure that’s not the topic of most TikTok videos nowadays, it’s a question civilizations have tried to answer throughout history. Many might say an army and wealth.

Although Genghis Khan built his empire initially with little money. He did have hell of an army. Instinctively, many put the focus here, and it makes total sense.

The Mongols had an all cavalry force, made up of talented horse-archers that could hit birds in flight. But this wasn’t unique in the Steppe. There were many horse-born armies from the Huns to the Scythians. However, they never had the long-term success of the Mongols.

Author, anthropologist, and professor Jack Weatherford sees something unique in Genghis Kha’s people. Namely, religion and their adopted written culture.

In his opinion, it takes more than a bow and horse to unite a globe-crossing empire. It takes the approval of heaven and an alphabet. But to understand the eventual empire, you must know its founder and the conditions that created him.

The Creation Of Genghis Khan

Before he was Khan, the leader of the Mongol Empire was named Temüjin and his father was a member of the royal Borjigin clan. However, his father died early. According to the Mongol text The Secret History of the Mongols, Temüjin and his mother were abandoned by their tribe.

His mother Höelün brought her young children off the Steppe and raised them on a mountain named Burkhan Khaldun. They were beyond poor. The family was subject to the cold and had to dig up roots or eat fish to survive. So, starvation and freezing to death were always a possibility.

As Temüjin reached his older teenage years, he sought out a girl his father arranged a marriage to when he was a child. However, a rival tribe noticed his new wife. They attacked Temüjin’s mountain home, and under the instruction of his mother, they abandoned his new bride.

This event made the boy realize he’d need outside help if he ever planned to regain his wife or achieve anything of significance.

Temüjin sought out a local tribal leader Ong Khan that was friends with his father, and a childhood friend named Jamuka. They agreed to help him. Not only did the union release his wife, but it also gave him a standing within the social world. Soon he had his own followers and tribe.

Weatherford calls them an “eclectic mix of individuals who had joined him willingly and some who had been taken as captives.” They represented different clans and religions. But Temüjin managed them all into one cohesive union which functioned.

Although his success caused internal problems.

Growing A New Empire From The Ruins Of An Old One

Weatherford says Ong Kahn and Jamuka came to see Temüjin’s tribe as an “uncouth band of misfits and renegades,” treating him like a guard dog that should be kept far away from their clean tribal centers.

Eventually Temüjin came into conflict with both and was initially defeated. However, he slowly attracted followers from the other side into his camp by diplomacy, leadership, and personality. He soon conquered his former leader and Jamuka. Then, defeated other major Steppe tribes.

By the early 1200s he gained the territory of the old Uyghur Empire, with the ruins of their capital Kharbalgas. Although small, it was grand to Temüjin, who was now crowned Genghis Khan.

The destroyed city had a temple, market, palace, walls, irrigation, and farmland that extended far in every direction. While the capital was abandoned, Uyghurs still lived in the area. Plus their culture lived on, with its religion and writing system.

Genghis Khan soon realized he’d never have an empire or capital city like Kharbalgas unless he adopted the structure of an empire. So, he picked up what the Uyghurs created.

Adoption Of The Uyghur Spiritual Practice And Text

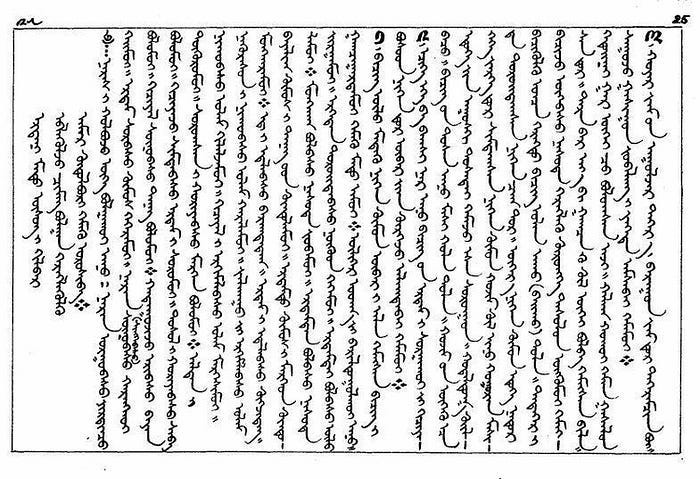

Genghis Kahn had literate members of his growing court work with the existing written language to create a “modified Uighur script”. The Mongols turned the original text from horizontal to vertical and read it from left to right, making it their own.

This enabled them to create a written system of law for the growing empire and communicate reliably over long distances. They also translated great works into Mongolian script.

Weatherford says a text about Alexander the Great and Aesop’s Fables were some of the first works converted. But the Uyghurs’ religious practices also interested the Mongols.

Kharbalgas was one of the few places Manichaeism was allowed to be practiced without persecution. Its odd nature appealed to the Mongols. This religion was created in Mesopotamia by Mani around 242 AD and was an attempt to combine the major religions of the time into one.

According to Weatherford, Mani “believed the divine spirit appeared in distant lands to teach in various languages.” This prophet thought God appeared in Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus. He also found God’s wisdom in ancient Greek philosophical teachings.

Weatherford says, “Manichaean cosmology and theology blended seamlessly with traditional Steppe spirituality.” The Manichaeans worshipped light, and the Steppe nomads had a special love of the sun, which reflected endlessly across their treeless realm.

The Manichaeans attempted to combine all previous religions “into one great sea,” just like Genghis Khan united the many tribes into one nation. They also divided their religious community into groupings of ten, which the Mongols adopted into their army.

Genghis Khan also liked their view of the law. According to Weatherford:

“Religion and the law cannot be separated. What was right, was sacred. What was holy was legal.”

In a sense, this religious view made the Khan “the soul of the state,” and his laws divine. Obviously, this was attractive to someone trying to keep together a multi-ethnic and religious empire under one nation’s banner.

It also gave Genghis Khan an incredible power.

Skepticism Of Spiritual Leaders

“The teeth in the mouth eat meat, but the teeth in the mind eat men.”

— Old Mongolian saying: Genghis Khan and the Quest For God, Jack Weatherford

Genghis Khan was left for dead with his mother and family at the decree of Mongol religious figures as a youth. And he never forgot this. The child Temüjin prayed to Burkhan Khaldun, the mountain of his refuge, and had no understanding of organized spirituality.

He’d later get his revenge, chewing up those like the ones who tossed him out.

As an adult, he managed a herd of outcasts with different backgrounds under his own law. The Mongols adopted Manichaeism because it had aspects which traditional Steppe people practiced, plus saw the wisdom of God in multiple beliefs.

However, Genghis Khan looked on religious leaders with skepticism.

If their God were truly powerful, Mongol armies wouldn’t be ravaging their lands. In their Manichaean belief, the Khan was a force of light, and those who resisted were in support of the darkness.

Plus, Genghis Khan looked at many religious leaders around him and saw frauds. So, he’d punish them personally — as a servant of God. While the early Mongol Empire respected most religious beliefs, the Khan was a subject of none. He created the divine law himself.

It’s ironic a text about Alexander The Great was one of the first translated into the Mongol written language. He also used religion as a base to grow his empire. Although Alexander chose to deify himself toward the end, so he could consolidate his multi-spiritual empire.

Genghis Khan didn’t become a god; he just decreed his law divine to create a structure strong enough to hold together his diverse nation. He also built a writing system to encode it.

So, it took more than an army to create the Mongol Empire. It required a strong spiritual leader that could create divine law with his own alphabet.

-Originally posted on Medium 5/8/23