“Alexander always respected the rules characteristic for the places he visited, so he descended his horse and went to greet the Jewish Archpriest. Alexander’s general Parmenion suggested that the soldiers were displeased that he greeted the… Priest first. Alexander answered that he didn’t greet the priest, but the God he represented.”

— Natalia Klimczak, Ancient Origins

How do you conquer the world? It’s one of those thoughts that doesn’t pass through the average person’s head as they sip their coffee. However, to many generals, kings, and emperors throughout history, it was an important question. Some even managed to do it — temporarily of course.

Alexander the Great captured an empire that covered three thousand miles by his early thirties. It combined the Greek, Persian, Egyptian, and Indian world in a conglomeration never before seen. Obviously, he did it with armies. But others had armies and never created an empire this far reaching.

What made this random Macedonian different? While it’s tempting to say tactics, formations, and leadership, it’s only one aspect. He had a far greater tool — religion.

Alexander worshipped and respected the local gods of whatever land he entered

Showed priests the utmost respect and followed their instructions to honor their deities

Created a cult-like group of followers or “Companions” around him, extending a tradition started by his father

Eventually deified himself, becoming a god in flesh

In many ways he wasn’t only a general or king, but leader of a faith — or perhaps faith itself. He’s often imagined on a horse leading charges. Although his greatest accomplishments were usually dismounted within various temples of the world he tried to conquer.

This faith proved to be a powerful weapon for the young king. But he could only wield it for so long. Eventually the sword of spirituality grew a double edge that began cutting into Alexander himself.

But before we get to his undoing, we need to start at the beginning: his father Phillip in Macedon.

The Cult Of Macedon

Kings of Macedon surrounded themselves with a close-knit group called “Companions.” According to the blog Operation Werewolf’s review of F.S. Naiden’s Soldier, Priest and God, Phillip changed the nature of this group.

Originally a club for nobles, Phillip turned it into a “religious guild for officers” that prayed, hunted, and went to war together. He also expanded its numbers, even to lower classes. Naiden notes it closely resembled a cult, and each member would fight and die for another member of this special group.

While Phillip turned into a mixture of lead hunter, king, and general, he respected his Companions, and often included them in decisions. This cult united king, noble-officers, and lower classes together through a religious devotion. It also strengthened Macedonia’s power and Phillip with it.

After Phillip’s assassination, Alexander earned the respect of the Companions by war, worship, and sacrifice. Naiden explains once he had his father’s place, Alexander planned a religious crusade to assume the throne of Persia, in the name of Zeus.

The same Zeus happened to be the “patron” of the Companions’ cult; all members swore a sacred oath to. Alexander cloaked himself in this devotion to the heavens like a suit of armor he wore to battle. This explains many of his actions on campaign.

Alexander’s Religious Armor

According to Naiden, Alexander performed many religious ceremonies before conducting any military operations.

His first act in Asia was to jam his spear into the earth. Religious ritual of the Macedonians dictated Zeus would award land to those who performed the act with the spear, then conquered it. Alexander also visited Troy’s ruins and made sacrifices.

Furthermore, the young king prayed to the heavens to justify his invasion and made sure his actions were coordinated with a religious calendar. To Alexander the gods of the local lands were just different forms of his own.

After his first victory against the Persians, he held religious ceremonies for the dead and visited temples in the land he won and worshipped local deities as directed. Alexander also created altars and sacrificed after his second victory at Issus.

Naiden notes part of the reason Alexander attacked Tyre was because the city leaders wouldn’t allow him to sacrifice at the temple of Melkart. Mainly because the ritual could bestow the legitimacy of kingship on the invader.

Alexander also made a dangerous trek with a small group of officers to a shrine (Siwah) in the Egyptian desert, almost dying in the process. Priests there rewarded him by telling the young man he was son of Zeus (or Amon).

Historian Natalia Klimczak at Ancient Origins says Alexander also visited Jerusalem, meeting with the Jewish priests and praying according to their instructions. They in turn showed him prophesies from the Book of Daniel saying a Greek would destroy the kingdom of the Persians.

While the conqueror carried the weapons of a soldier, he also won the acceptance of the local versions of his own gods — wearing the authority of the heavens like a crown. But this was only the beginning.

Alexander Becomes A Deity

“It was not so much for a man to be a god in the Greek sense of the term. The chasm between humanity and deity was not as wide then as it was to become in modern theology.”

— Will Durant, The Story of Civilization (The Life of Greece)

According to historian Will Durant, Alexander sent a decree to all Greek states in 324 BC announcing he was son of Zeus Amon. Surprisingly, most Greeks didn’t care. Even the religious Spartans accepted the announcement — almost rolling their eyes, in an antiquity-style “whatever.”

The Persians also didn’t mind prostrating before a god-king. Durant notes the Egyptians might even think it strange if a leader didn’t declare himself a god. After all, what was the pharaoh?

But the decree skipped one region: Macedon. Durant explains Alexander did this to avoid annoying those who were loyal to the memory of his father. However, it also violated beliefs of his current cult of the Companions.

They wouldn’t fall on the ground and worship their equal. This created stress between Alexander and his Companions, even instances of rebellion broke out.

While the king’s ego did get stroked by the declaration, Durant believes it more political ploy than Alexander truly believing himself a god.

The historian notes the young man joked at blood shed from wounds he received and his need for sleep. Both aren’t trappings of a god.

The god-king also continued to worship other gods in public — odd behavior for a deity.

Alexander was well-versed in the power of religion. What better tool to unite worlds “hostile” to each other, such as Greece, Persia, Egypt, and India?

The Macedonian also understood cults well, so he created a new one, with himself as the center. Durant describes it as a “common unifying faith” or a “sacred myth.” Think of it as an adjusted version of the Companions.

Unfortunately, the deity died about a year afterwards. Although, in many ways, he never left.

The Sacred Myth Of Alexander

“Men judge more by appearances than by deeds. Everyone can see, few people can actually perceive and judge. Everybody can see what you seem to be; few can judge what you actually are.”

— Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

While Alexander wasn’t a god, he successfully made his new cult. He created an aura around himself so great his generals fought over his body in order to use it as a symbol of approval for their reign.

Ptolemy set up a shrine to his former boss in Egypt, which gave his bloodline legitimate authority of a deity to lead the land for about two hundred years. Even Romans visited and honored the shrine.

The Macedonian became the most famous person in history, captivating minds for thousands of years, even modern ones. Jim Morrison of the Doors copied his appearance, Julius Caesar longed to equal his accomplishments, and a recent Marvel series’ hero explored Alexander’s lost tomb.

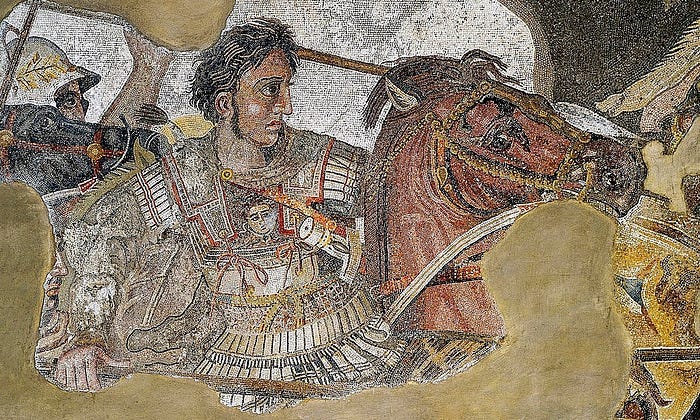

The picture above might be the most famous representation of the former king, but its military aspect is only a small vision of the man.

While most associate the words “conqueror” and “phalanx” with Alexander, these weren’t his most powerful tool. It was faith. The leader understood better than most the power of religion in a world with no atheists.

He also became more than just a king for his followers. Alexander made himself into a sacred myth — one that lasts to this very day in our culture, language, history, and fiction.

I learned more about Alexander from this article than I have learned before. And what I learned ties in with my thoughts about exercising power, largely formed from reading Lord Acton. It actually expanded my understanding of power. In a genuine way, Acton's pronouncement that power tends to corrupt, and Alexander's self-deification are reflections of each other. I have a theory that said corruption happens to both the wielders and the subjects of power. Those who submit to exercised power become corrupted by their submission as do those who exercise it.

Incidentally, at the heart of the corruption of all organized religions, including Christianity, is the exercise of and the submission to the power of religious men.