What Was It Like To Fight In A Greek Phalanx?

The technology of a solid human wall of spears and shields

It wouldn’t be long. Standing in the dead center of the phalanx, reality starts to settle in. People are going to die today, and they’ll be those you know. Maybe even yourself. The battle will begin shortly, but no one is truly ready.

The pee running down the leg of the man to your left makes it all too obvious. He’s a baker, not a warrior. On your right a famous poet — again not a soldier — and you can hear his knees knocking together in fear. You’ve all trained for this day with your city, but it can’t prepare you for the harsh reality.

The heavy armor you wear is taxing. The giant shield you carry is supported by your shoulder and might be the most important piece of all. Despite its size, it doesn’t cover your whole body. You’ll need the shields of the men to each of your side to protect you — those carried by the knee-knocker and the pisser.

The sun shining, birds chirping, and the pleasant Mediterranean day doesn’t improve your mood. Then, your heart stops. You see the enemy phalanx and part of it is clothed in scarlet red. The Spartans are with them. You’re screwed. You try and pray, but you’re so terrified, the words escape you.

This is a quick glimpse into the world of the ancient Greeks and their phalanx military formation. You’ve seen it in movies. Plus, the term has been tossed around in many of your history classes. But what is it, and how did it work?

First of all, think of it as a technology, not just a formation. Let’s start with the base unit: the hoplite.

The Hoplite Infantry Unit

Over the years, I’ve watched several television shows matching historical fighters. Usually in a one-on-one sense. It’s almost like a video game approach — comparing armor, weapons, and prowess versus another warrior from a different time.

You can’t exactly do this with a hoplite. Well, more precisely a single hoplite.

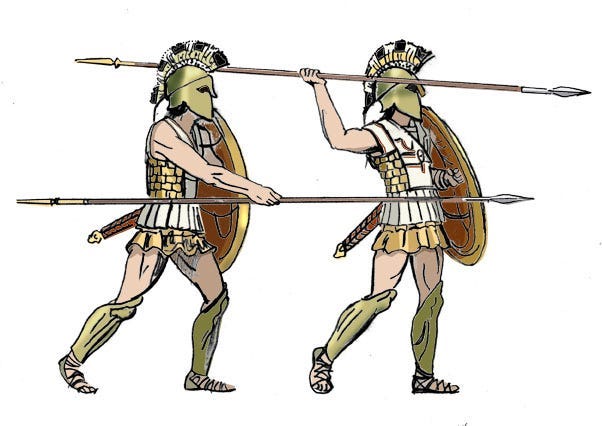

According to historian Victor Davis Hanson’s book A War Like No Other, a hoplite alone was an easy target. They sacrificed mobility for protection. The average hoplite wore about seventy pounds worth of armor and gear. So, a lone hoplite was cumbersome, but put them in a tight formation (phalanx) while carrying spears and they became a military system.

While a warrior is generally known for the weapon they carry, the hoplite was more known for their shield, the hoplon. If the two words sound similar, it’s for a good reason. You can’t have the hoplite without the shield.

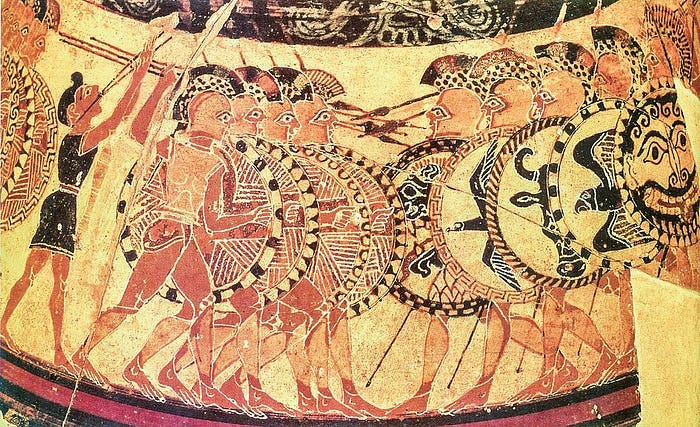

Mark Cartwright at the World History Encyclopedia says the circular hoplon weighed about eighteen pounds and was thirty inches in diameter. The shield had a band called the porpax the entire arm went through, and a handgrip named the antilabe at the edge. It was usually made of wood or leather and covered in bronze.

The shield was easy to carry and hard to drop by design. A hoplite’s shield couldn’t protect them entirely, so they needed part of the shield from the man on their right to cover themselves.

A phalanx couldn’t exist without the shield. In fact, Andrei G. Zavaliy in his book Courage and Cowardice in Ancient Greece says one of the greatest insults in ancient Athens was to call someone a “shield thrower”. Even the columns in the phalanx were referred to as “x shields deep,” not “x men deep”.

According to Hanson, each hoplite equipped themselves with a breastplate, helmet, and grieves (shin protectors) usually made of bronze. This set, called a panoply, cost about three months’ wages. So, usually the middle class or higher made up the phalanx, and it wasn’t unusual for the citizen-soldier to hand the set down to their children.

This hoplite also carried a wooden spear, which Cartwright mentions was about eight feet long and featured a bronze or iron point. It also had a spike (sauroter) on the back. Their secondary weapon was a short iron sword, no more than two feet long.

The Phalanx As A System

“Killing a man in full bronze armor — breast plate, helmet, and grieves — was not an easy task, especially when all hoplite’s first concerns were to keep close to one another and have their wooden shields locked in a near wall of defense.”

— Victor Davis Hanson, A War Like No Other

Hanson says the average Greek hoplite didn’t try to “rack up kills through individual prowess,” but marched in complete unison to “defend, push, and kill anonymously as the collective body moved ahead in rank and formation.”

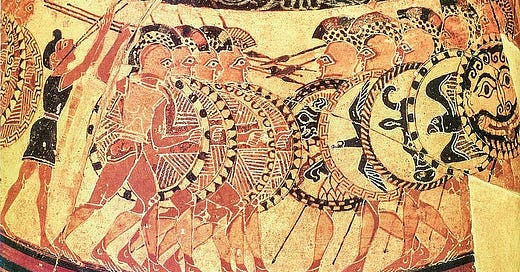

The grouped column of men was said to resemble a bristling porcupine with its spears sticking out as it moved.

Surprisingly, casualties were relatively low in phalanx battles. Usually no more than ten percent of the group were severely wounded or died. The quarter inch thick armor and tight shield formations could ward off many random blows. Plus, more than half the formation couldn’t touch the enemy phalanx with their spears at any given time.

Engagements usually ended quickly and there were few instances of traditional hoplite battles stretching for days. According to Hanson, sometimes the affair could break up in a matter of minutes, especially if fear or “phobos” settled in causing a formation to break up.

The traditional phalanx formation was made up of three blocks: left, center, and right. Generals and usually the best soldiers comprised the right wing, while the weakest went to the left. The center was the biggest block.

Hanson says these battles were usually a test of which right wing could break through first and blast the next set of columns over in their flank. There were no advanced tactics till much later. It also wasn’t shocking for a general to die in combat.

Tactics were limited due to the chaos when phalanxes crashed together. The heavy bronze helmets limited vision and sound. Plus, dust kicked up as well. Hoplites in the center of a column were likely getting squished in every direction — front and back. Think of it like a rugby or American Football scrum with weapons and armor.

Hanson also points out it wasn’t unusual for “friendly fire” incidents where a cities’ hoplites would attack their own forces because most were equipped with very similar gear. Plus, once a phalanx broke, soldiers could jettison their gear and run.

They mostly escaped because the advancing soldiers were too weighed down to chase the unencumbered men.

What Was The Point Of This Type Of War?

The overall Greek population was divided into various city-states with shifting alliances and changing territory. So, war over boundaries was a frequent occurrence. A phalanx enabled a citizen-militia to be formed into an effective military unit with little training and expense.

Citizen-soldiers could battle one day, then go back to farming the next since phalanx battles were over quickly.

It also allowed war with few casualties. Hanson says while hoplites physically engaged took constant spear blows, their only vulnerable areas were their neck and groin — small targets.

In fact, most Greek cities didn’t start building walls until after the Persian invasions. Phalanx battles were usually fought — almost ceremoniously — at arranged times on designated pieces of land. Also, calvary was pointless in most city-states. It was far too expensive to raise horses in mountainous Greece.

In other words, the phalanx was a technology which worked well to deal with the unique political and geographic structure of ancient Greece.

According to Hanson, it didn’t change much until the Peloponnesian War when it was exchanged for mostly light infantry and fleet battles. But the phalanx would be modified and come into prominence once more under the Macedonians.

So, what was it like to fight in a Greek phalanx?

Chaotic and quick. But the terror of the one day in the phalanx enabled smooth and peaceful lives to continue in ancient Greece.

-Originally posted on Medium 11/21/21