Those Who Study the Past May Be Fortunate Enough to Repeat It

History provides us with a missing consistency in an ever-changing world

The Ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus once pondered that the only thing constant is change.

Today, as with most things, we’re taking this to extremes. The present information revolution — made up of its ones and zeros — is displacing the industrial revolution’s machines and Neolithic revolution’s society at the blazing speed of a neural network.

Now Heraclitus’ change is happening so fast, the time around us seems like an endless technological revolution. I got a quick glimpse into this whirlwind today. It came in the form of a press release.

Google’s AI lab, DeepMind, proclaimed to the world that it created an AI system called AlphaProteo that can design novel binding proteins. Why is this important?

Well according to DeepMind, these protein “binders can help researchers accelerate progress across a broad spectrum of research, including drug development, cell and tissue imaging, disease understanding and diagnosis — even crop resistance to pests.”

Currently scientists can develop these proteins, but it’s laborious and expensive. In tests, AlphaProteo is designing binding proteins with “3 to 300 times better binding affinities than the best existing methods,” and higher overall success rates.

As could be imagined, the AI system does it faster too. This opens a door to possibly manipulating life itself and bioengineering our world and selves in unprecedented ways. How’s that for change? And it’s only one of many coming our way.

While this is exciting — and terrifying — how do you mentally live in a world of cataclysmic shifts where you can’t recognize your world from day to day?

Drugs may do the trick for some, but I’ll put my faith in history. Although it’ll require a change in our traditional view of the subject.

Changing The Traditional View of History

The philosopher and critic George Santayana is credited with the saying, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” which every history teacher is required by a hidden force of nature to remind their students.

For many, that’s all history is. It’s war and an endless series of people being awful to each other, along with nonstop tragedy. So, as a subject, it’s an instruction list of what not to do for a society. But what if it was more?

Historians Will and Arial Durant see it differently. In their book The Lessons from History, they remind us history can be a beautiful learning tool. They say:

“To those of us who study history not merely as a warning reminder of man’s follies and crimes…the past ceases to be a depressing chamber of horrors; it becomes a celestial city, a spacious country of the mind, wherein a thousand saints, statesmen, inventors, scientists, poets, artists, musicians, philosophers and lovers still live and speak, teach and carve and sing.’’

The couple reminds us that history as written is usually different from history as lived. Like the nightly news in our time, terrible things make the headlines.

“Behind the red façade of war and politics, misfortune and poverty, adultery and divorce, murder and suicide, were millions of orderly homes, devoted marriages, men and women kindly affectionate, troubled and happy with children.”

There were also fantastic minds, larger-than-life characters, and personalities and ideas that defy time and age. They also defy change. If there was ever an anchor to keep you moored against the ravages of the information revolution, history is it.

Moreover, there are plenty of examples of history as this anchor and making its shadow present in the modern age.

The Warriors, Singers, And Soldiers

Megiddo is a place that’s name is often mentioned in history. From it derives the term Armageddon (as in the place where God and Satan will battle it out at the end of time according to the Bible.) But Megiddo was famous before it was ever written about in this holy book.

Sometime around 1458 BC, Pharaoh Thutmose III marched 150 miles to Megiddo (in present day Israel) to deal with an insurrection as the monarch ascended to the throne. As they got close to the site, the Egyptian army rested in Gaza.

Thutmose’s scribe, Tjaneni, records the Pharaoh and his generals discussing the best way to approach Megiddo.

There were two easy approaches where the road widened, and the army could span out. Plus, one narrow pass of difficult terrain where the soldiers would have to march in single file and could easily be ambushed. The generals recommended the easy paths.

However, Thutmose insisted on choosing the difficult passage.

The monarch believed his enemies would guard the easy roads, but would never expect the Egyptians to be dumb enough to take the narrow pass. It turns out Thutmose was correct and bypassed an ambush, then crushed his enemies.

About 3300 years later, British General Edmund Allenby sat in front of the same sets of roads, heading for Megiddo while fighting the Turks during World War One.

In The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age, Professor Eric H. Cline quotes a conversation between Allenby and archeologist James Breasted after the war. According to the General:

“You know, I went straight through the Pass of Megiddo…Curious, wasn’t it, that we should have had exactly old Thutmose’s experience in meeting an outpost of the enemy and disposing of them at the top of the Pass leading to Megiddo!”

So, the general knew of the historical significance, and copied the Pharaonic playbook to the same results. But historic themes often retain their punch in the modern world.

In the late 1970’s a film called The Warriors became an all-time cult classic. The movie revolves around street gangs in New York City. After the death of the largest gang leader in the city, a gang from Coney Island is framed for the murder.

This gang, The Warriors, is now stuck in the middle of New York City, surrounded by hostile gangs, and must fight their way home. Little did audiences know, the writer didn’t invent this tale.

It was based on ancient Greek general Xenophon’s Anabasis, or March of the Ten Thousand. In this tale, Greek mercenaries support a rival to the Persian throne for money. But their paymaster gets killed in a battle and the Greek mercenaries are left stuck in Persia and must fight their way out. According to Steve Coates in the New York Times:

“It’s amazing how apt the gang motif is for Xenophon’s work, both in terms of the diverse, exotic, often fierce inhabitants of the Persian empire (freely translated on film into Baseball Furies, High Hats, Electric Eliminators and so forth) and of the Greeks themselves. ‘The Ten Thousand were a gang of roughs,’ George Cawkwell writes in his introduction to the book’s Penguin edition…”

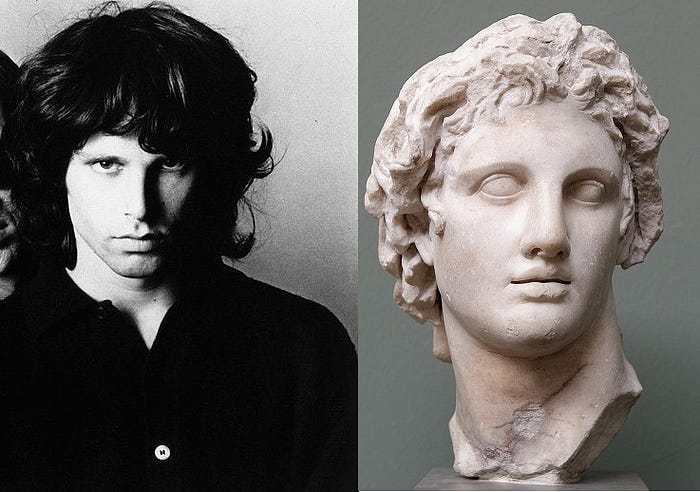

Furthermore, while Jim Morrison, lead singer of The Doors, may be thought to be a unique character. His style was copied.

According to Glenn D. Walters’ book Lifestyle Theory, Morrison copied his iconic hair style from Alexander The Great. He’d even cock his head like the emperor from his famous portraits and statues.

While these are all relatively random examples, it does demonstrate a concept that can be expanded upon.

The Opportunity When The Unchanging Becomes A Rarity

Now, what have we learned so far? Well, our present world is one of endless change that resembles a nonstop revolution. The past is also more than a “depressing chamber of horrors,” as the Durants remind us, and its ideas still remain highly relevant in our world.

This configuration presents an opportunity. If you can combine this lack of stability with the evergreen appeal of history, you can fill a needed niche that’s currently desired.

With that said, let’s give AlphaProteo and the AI mob their space. The information revolution can rage on. But the Heraclitus-on-overdrive nonstop change leaves the human mind, soul, and heart looking for something to hang on to.

This is where history comes to the rescue. It’s the historian’s (or amateur historian’s) task to revive the things that never change and to relieve the restless folk worn out from the mind-numbing ones and zeroes.

Therefore, with all due respect to Mr. Santayana, his famous quote, and every history teacher I had in school, those who study the past may be fortunate enough to repeat it.

-Originally posted on Medium 9/8/24