This Monument’s Completion Is Marked On A 26,000-Year Star Map

The barely noticed dedication challenges our standard idea of time with science and art

“The historic mission of sculpture is…to evoke a pungent realization of man and to make this realization nearly imperishable against the oblivion imposed by time. It may also shape a symbolism in human form in order to convey the very best within the reach of the aspirations and endowment of the race.”

— Oskar J. W. Hansen, Sculptures at Hoover Dam, US Bureau of Reclamation, 1978

We currently have a short-sighted view of time. I think it derives from two factors: our limited lifespans and the units we regularly use to measure time.

The average human life lasts less than a hundred years. Because this period is so short, we’re attracted to measurements like seconds, minutes, hours, and years. These are ideal for tracking our birthdays and important life events.

However, they lose something in translation when we calculate much greater ages. For instance, the earth is thought to be 4.5 billion years old. That’s so far from our standard human use of time that it’s almost incomprehensible.

Although we don’t have to go back that far, human-made monuments can also defy our current comprehension of time.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is thought to be 4,500 years old.

Göbekli Tepe in Turkey may be 11,000 years old.

The Roman Colosseum is over 2,000 years old.

These great architectural art pieces were built out of materials designed to live long past the lifespan of a human or even a nation. They were created to contend with time itself in its immortal march. A famous artist remembered this when he was hired to work on a modern wonder.

The Hoover Dam was this project, and Oskar J. W. Hansen won a national contest to create a sculpture celebrating its construction. But it was no ordinary dam.

According to the US Bureau of Reclamation:

“Hoover Dam was the first man-made structure to exceed the masonry mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The dam contains enough concrete to pave a strip 16 feet wide and 8 inches thick from San Francisco to New York City. More than 5 million barrels of Portland cement and 4.5 million cubic yards of aggregate went into the dam.”

This was a functional monument on par with the great works listed above, which have lasted for thousands of years. Hansen considered this. The landmark needed an artistic representation of time beyond human years.

Hansen marked the exact date of Hoover Dam’s dedication with the help of a Platonic Year (now known as the Precession of the Equinoxes), a nearly 26,000-year star cycle the Earth repeats. He turned this into an artistic star chart.

Most likely have never heard of this cycle, so it’s best to understand the heavenly phenomenon to better comprehend the artistic representation.

The Precession of the Equinoxes

So, how does this cycle work?

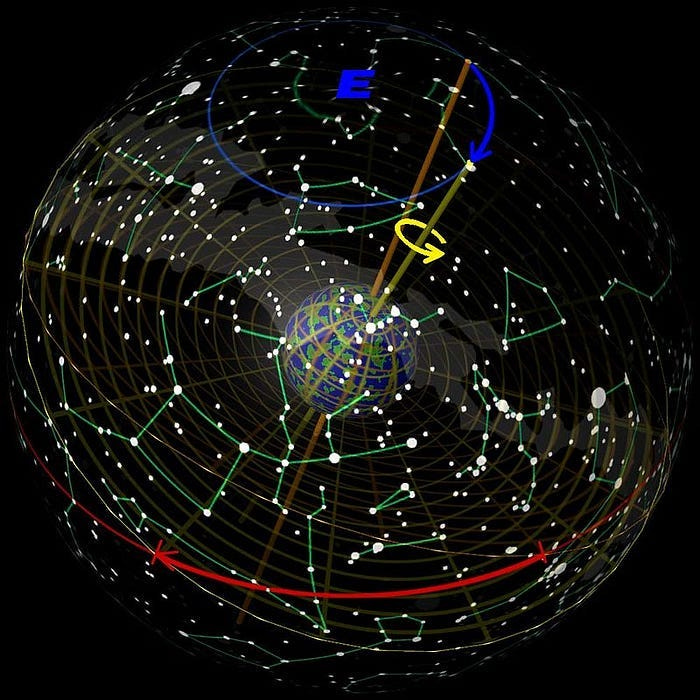

First, let’s imagine the Earth for a second. You know it rotates — obviously, since we have day and night. However, the Earth is also tilted as it spins on its axis. Think of a top or bottle cap’s spin right before it falls. If you put an arrow at the top of the planet, it would draw a circle around a selection of sky.

As the astronomy department at the University of Lincoln Nebraska points out, the Earth’s orbital tilt is 23.5 degrees. This is because our planet isn’t a perfect sphere. It’s got some baby fat around its middle. The gravity of the Sun and Moon pull against this, pushing our imaginary arrow at the top of the planet to wobble and trace out a cone.

The cone is complete in about 26,000 years. So, although it may look like the stars are moving, it’s really Earth completing a rotation of sorts. The Encyclopedia Britannica explains that Hipparchus discovered this phenomenon in 129 BC. The Greek astronomers noticed different star positions from the earlier notes the Babylonians took. So, our closest Polar Star changes with this advance.

The orange pole angle below indicates where Thuban was about 5,000 years ago (the pole star used to align the Great Pyramid.) The green suggests where Polaris (our pole star) is now. Eventually, this angle will change again, giving future humans another north star. However, in between, there may be periods where there is no true north star in position as a guide.

Now, here comes the interesting part. How do you mark a date with something this complex in a chart near a functional dam? Well, you need a determined artist.

The Monument Within A Monument

Hansen didn’t just create a star chart; he created a monument within a monument. The black stone where the bronze figures and flagpole sit is diorite, an igneous rock quarried in California. Hansen says in Sculptures at Hoover Dam that this rock was a favorite of ancient Egyptian artists.

But it can be easily marred. To avoid this, construction crews laid this rock base on ice blocks and slowly guided it into place as they melted. The black flooring it sits on is terrazzo. You can see the star chart up towards the base, but we’ll get to this in a minute.

In the center of the diorite block, you’ll notice a pole. It’s a flagpole with an American flag that stands 142 feet high. This was dropped through a hole dug in the diorite into a specially prepared socket cut into the mountain. Keep the flagpole in mind. It serves a special purpose.

Our next pieces are the “Winged Figures of the Republic.” These statues are 30 feet high and molded with 4 tons of statuary bronze with 5/8" thick shells. Hansen wanted them to have facial features resembling eagles.

They sit in contemplation but have hands and wings raised, ready to move at a moment’s notice. Hansen says, “The Winged Figures of the Republic give evidence to the thought which preceded the reality of Hoover Dam and to that eternal vigilance which is the price of liberty.”

The central theme of the entire section is the star chart, which unfortunately gets overshadowed by the largeness of everything around it, although the chart has a brilliant magnitude of its own.

The Star Chart

“Time, the intangible governor of all our acts, is measured to us by the external relations of our Earth to other worlds in space. Therefore, I thought it fitting to have the base of the monument rise from a finely wrought, marble terrazzo star map of the northern regions of the sky.”

— Oskar J. W. Hansen, Sculptures at Hoover Dam, US Bureau of Reclamation, 1978

According to Michael Hiltzik in Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century, Hansen spent three years working on this star chart, aided by “an intricate framework of compasses, calipers, and protractors, shunning conversation with inquisitive onlookers.”

Hansen used the flagpole to mark the sun's position within the chart. So, on the dedication day of the dam, September 30, 1935, the pole pointed directly at the center of our sun.

The artist says the black circle with the white wedge (above) “indicates the diurnal rotation of the Earth on the day of the Dam’s dedication.” In other words, on this 26,000-year chart, you can calculate the year, day, minute, and second the dedication of the dam took place. But that’s not all.

There are also momentous times in human history marked on the chart.

The position of a pyramid is also marked when Thuban was the pole star of the ancient Egyptians. The birth of Christ is also marked midway between Thuban and Polaris. You can also find Vega, our eventual pole star, by continuing to walk around the base.

Various stars’ magnitudes (sizes) are also shown, as the human eye can see them 10 parsecs from Earth. A parsec is roughly 19 trillion miles. However, the true distance is closer to 50 parsecs (Hansen magnified it for us, so we could see it better.)

The artist also sought expert calculations to configure the chart. According to Hansen, using “the calculations of the Naval Observatory, the Smithsonian Astrophysical Laboratory, and other authorities,” he “placed the bodies of our solar system in the terrazzo, correct to the minutest fraction of an inch in the scale of design.”

So, Hansen’s monument not only marks the dam's dedication but also reflects this within an astronomical phenomenon, which covers a 26,000-year cycle. It also makes us reevaluate our short idea of time.

Time Beyond A Human Scale

Right now, I’m staring at my clock. Like most, I work on short time scales, planning my days and weeks on 24-hour blocks. Time doesn’t exist like this for monuments, planets, or astronomical cycles. They live on a much longer basis.

At Hoover Dam, Hansen reminded us of this by invoking materials used by the ancient Egyptians, noting their pole star was different from ours on his stellar chart, and highlighting the 26,000-year Precession.

He used a combination of science, art, and imagination, much like Da Vinci used knowledge gained from anatomy and mathematics to paint The Last Supper.

Combining all these elements into an art piece gives us aesthetic beauty and stretches our mind around the temporariness of our lives compared to the stone monuments we leave behind.

In the US Bureau of Reclamation guidebook I’ve referenced several times, Hansen admits that while few may be able to navigate a ship or calculate true time, most can read the face of a watch. He set his star chart up like this.

I think it’s one of those beautiful combinations of art, science, and engineering you rarely see anymore. It’s an accumulation of all that makes us human.

Hansen’s work also challenges our 24-hour cycle thinking with a much longer view of time, like those incorporated into Göbekli Tepe, the Great Pyramid, and the Roman Colosseum. Although many may miss it due to the grandeur of the dam itself.

-Originally posted on Medium 5/14/24

The precession of the equinoxes traces many changes in humanity across the illusion of linear time.

https://open.substack.com/pub/clementpaulus/p/recursive-tension-as-method?r=5c1ys6&utm_medium=ios