This 160-foot-tall Mountain Of Trash Tells Us A Secret About Rome

Monte Testaccio hides details about a great empire

“Like us, the Romans enjoy the dubious distinction of creating a mountain of good-quality rubbish.”

- Fall of Rome: And The End Of Civilization, Bryan Ward-Perkins

You can learn a lot from trash. For instance, when police investigate a suspect, they can piece together many details by diving through their waste cans. Historians are doing the same thing with ancient Rome.

The picture above shows a landmark near the Tiber River's banks called Monte Testaccio. It looks like nothing special. However, despite the trees and grass growing on this inclined slope, the one-hundred-sixty-foot-tall mountain is man-made.

In his books, historian Bryan Ward-Perkins says the mound is made up of fifty-three million amphorae, or jugs, stacked up over a period of about three hundred years. The name Monte Testaccio is roughly translated as “pottery mountain.”

Furthermore, Perkins believes these containers once held billions of liters of olive oil. If so, the scope is astronomical, but don’t get lost in the numbers. There’s more to see here.

These remnants also allow us to make our best police-dumpster diver impression to better study our Roman subjects. This massive dump can tell us much about their economy, infrastructure, government, and society. It also hides a secret about what they feared.

We’ll start with a simple question: what’s the deal with billions of liters of olive oil, and how do you get that much product to Rome?

Olive Oil’s Importance And The Roman Transport System

In Andre Curry’s article in Science, he says that olive oil was beyond a condiment in the Roman Empire. It was a proper ingredient in just about everything. Bodies found at Herculaneum (destroyed by Mt. Vesuvius in 79AD) got at least twelve percent of their calories from olive oil.

It’s also believed that the average Roman consumed twenty liters of the product yearly. But it was used for more than food.

Yolanda Peña Cervantes says it was an ingredient in perfumes, used as a medicine, a staple in religious rituals, and even burned to light homes and temples. In her interview in the BBC, the professor of archaeology at the National Distance Education University notes a primary source for Roman olive oil was a province called Baetica.

This encompasses modern-day Andalucia in Spain, which still grows olive trees today. The region currently has five to six thousand olive trees over a thousand years old. A few of these trees are even two thousand, and they were living during the Roman Empire.

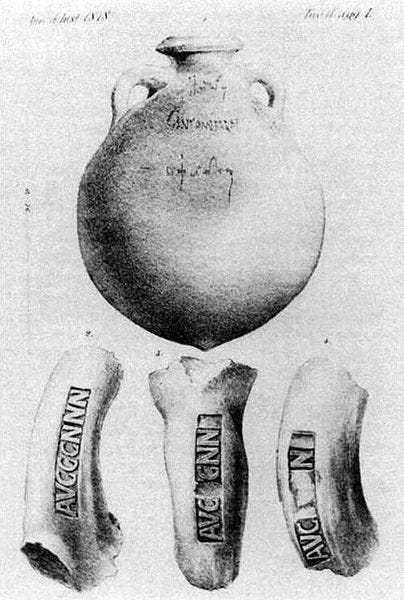

As these long-lived fruit producers show, olive trees are hardy and can withstand harsh conditions. In Roman times, olives were picked from these trees and ground down into olive oil locally. The finished product was placed in special amphorae, now termed “Dressel 20.”

The Society of Antiquaries of London describes this particular amphora as follows:

“A very large, rounded vessel with two handles and a thick, rounded, or angular rim. Manufactured in Spain from the later 1st century AD until the 3rd century AD, Dressel 20’s were transport vessels used to export large quantities of olive oil throughout the Roman Empire. This type of vessel would contain between 40–80 liters of olive oil.”

These large jars were also easily transportable over water. The Romans had an incredible network of river systems with specially designed boats that could carry sizeable cargo across the empire directly or to and from ports. Many of these products found their way to the city of Rome itself.

Wood from Gaul made its way across river networks to become the foundations of Roman homes.

Obelisks weighing hundreds of tons from Egypt were transported across the ocean to Rome’s shores, where they were transferred through their river networks up the Tiber and into Rome.

Some fifty-three million Dressel 20s sailed overseas, then finally rivers, ending their trip as empty vessels by the banks of the Tiber.

While this answers the why and how of the large quantities of olive oil, there’s still curiosity about Monte Testaccio. Why build a mountain out of amphorae?

Amphorae, Economics, And The Building Blocks Of A Mountain

Archeologist and ceramic expert J. Theodore Peña says anywhere from eighty to a hundred percent of Monte Testaccio by weight is made up of Dressel 20s from Spain. These amphorae could only be used once due to their absorbent nature and were disposed of afterward.

In Roman Pottery in the Archaeological Record, Peña says the Dressel 20s were only vessels for transport. Once the oil arrived, it was transferred into smaller containers. This left the issue of what to do with the jugs.

Monte Testaccio began as a dumping area on the eastern side; however, around 140 AD or so, an organization of the western side of the mound began.

The entire Dressel 20s were laid down with their mouths facing the outside of the mound, their bottoms broken open, and the vessels filled with broken shards of other amphorae. This acted as a wall, while shards were filled behind to the height of the Dressel 20s. This process was then repeated.

Each layer was slightly smaller as the mound went up, making a pyramid-like structure. It appears up to four layers were created, and then, around 220 AD, dumping shifted back towards the eastern side again. Lime was also sprinkled over the shards to remove any smell.

The amphorae themselves tell much due to their titulus pictus. Peña says this type of stamp or mark acts as a label giving the following information.

The weight of the amphora and who weighed it.

The region the product came from.

It can also indicate where it is going and what its purpose is.

In this case, a significant amount of the tituli picti (plural) found at Monte Testaccio indicates this oil belonged to the state. It was part of the oil dole. While many know the Roman Empire gave grain to the populous to keep them calm, they did this with oil too.

So, with this mound of crushed amphorae the size of a mountain, one could only assume this was a massive government expenditure. Now, put your police hat back on for a second. What does all this information we just learned from dumpster diving tell us about Rome?

What A Large Mound Of Trash Tells Us About The Roman Empire

Monte Testaccio tells us a lot about our subject. First, we’ll start with the importance of olive oil in Roman life. It wasn’t just a condiment for food but a main ingredient in food, medicine, perfume, religion, and even fuel.

For them, olive oil was life.

Second, we’ll move to the empire’s infrastructure. It was a fantastic economic machine, with arteries made of water, which coursed products and goods from one end to another efficiently and quickly. Let’s examine this using Bryan Ward-Perkins’ calculations.

53,000,000 amphorae over three hundred years equals about 176,666 Dressel 20s brought in annually.

If you conservatively say each jug held forty liters of olive oil, then the amount of product brought in annually was 7,066,667 liters. It’s double this if you assume each Dressel 20 was filled to the top.

These staggering numbers display Roman economic might, but there’s a secret within them. Think about it for a second. A significant portion of the olive oil trade at Monte Testaccio was for the government to distribute to the Roman people.

Why would they do that and go to all that expense?

With Rome’s massive armies and enemy populations situated around their borders, you get the impression their greatest fear was an external enemy. However, a little police work in a massive pile of trash shows differently.

When I put on my detective hat, I could see that the Emperor and government feared Rome's population the most. Historian Barry Strauss confirms this saying at least nineteen food riots are recorded in Rome, one of which caused emperor Claudius to run to save his life.

The saying “bread and circuses” has become an infamous meme throughout the ages, referring to Rome’s method of distracting an unhappy populace with trivial things. Perhaps we should say bread, olive oil, and circuses instead.

Like I said, you can learn a lot from trash.

-Originally posted on Medium 7/23/24

Thanks for posting here. I've given up on Medium, though I still have an account on that platform.