The Largest Explosive Disaster Until Hiroshima

It happened right on the East Coast of North America

“Chebucto School was turned into a morgue. I can remember seeing low sleighs piled high with the load covered with tarpaulin. The tarpaulin didn’t hide the fact that the load was bodies. I thought that all the legs and arms were covered with black stockings. It was years later that I realized there were no black stockings — that was burned or frozen human flesh. I remember this very vividly but at the time I did not realize the significance of what I was seeing. It didn’t upset me. This instance and the story of my Mother’s distorted face, make me thankful that I was too young to remember details and realize the horror of what I saw.”

— Jean Holder, Halifax explosion survivor, recorded 6 December 1985. Nova Scotia Archives MG 27 volume 9 number 4.

On November 19, 2019 a Christmas Tree arrived in Boston all the way from Nova Scotia in Canada.

The large tree’s arrival was a community event; people from all the region came to greet it. However, this wasn’t a marketing event for a Hallmark Christmas film. This gift was to commemorate a kind act from the people of Massachusetts over 100 years ago.

You might be thinking, what type of kind act garners 100 years’ worth of gratitude? The act was a quick response to a 3,000-ton sea-borne bomb which exploded in Halifax December 6, 1917.

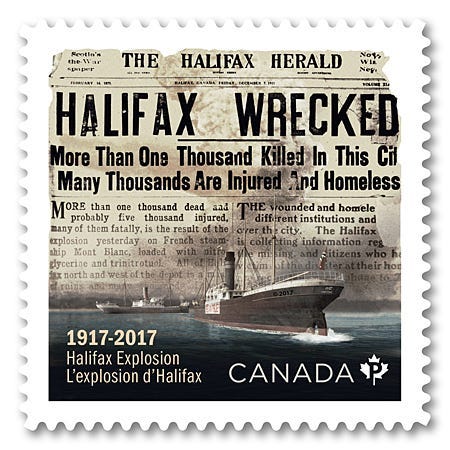

This wasn’t a mere accident which catches attention and headlines. The explosion literally leveled an entire city and killed thousands of people. Steve Hendricks of The Washington Post referred to it as “unsurpassed as an explosive disaster until Hiroshima replaced it in 1945”.

The description given by survivors immediately sends a certain eerie chill down the spine of a modern American. A survivor named Harold Connolly described the relief experienced by those who found missing loved ones in hospitals and the uncontrollable grief when their bodies were discovered in make-shift morgues.

One can’t help thinking of despondent New Yorkers searching for missing loved ones after 9/11, some even posting pictures and names waiting for any news. In a way, the disaster in Halifax was Canada’s 9/11 over 100 years ago. It was this type of environment which inspired the tradition of sending a large Christmas tree over countless miles and years, continuing to this very day.

The Event

Halifax had always been an important harbor, particularly in wartime. It was almost as if nature itself went about designing the perfect port: deep waters, doesn’t freeze over, and right on the Atlantic Ocean facing Europe.

According to a research document created by NASA, Halifax had been used as a hub for war supplies during the American Revolution, The Napoleonic Wars, The War of 1812, The American Civil War, and eventually World War I.

The natural harbor had been flooded with traffic and the small city of Halifax ballooned to a population of 50,000. It offloaded and uploaded everything from wounded soldiers, to supplies, and even vast quantities of ammunition.

It was also a meeting point for convoys on their way to the European theater of operations. As a result, the harbor was also an ideal target for German U-boats, but again the port designer mother nature created a geographic deterrent.

A small choke point called the “narrows” connects the outer harbor to the inner basin area. Human engineers took advantage of the tight geography to make a submarine net to keep the unseen German sharks out of their pool. However, this tight area combined with large ships under demanding schedules made eventual collisions a likely probability.

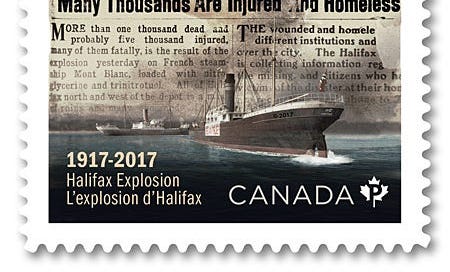

A French Vessel called the Mount-Blanc entered the narrows on December 6th, carrying over 2300 tons of picric acid, which NASA pointed out is “more powerful and volatile by weight than TNT”. In addition, it carried 250 tons of TNT, almost the same weight of benzene, over 60 tons of nitrocellulose, plus about 300 rounds for the deck guns mounted on the ship.

A ship of this nature usually carried a flag indicating its deadly cargo, but these were removed so they didn’t tip off U-boats in the area. A Norwegian ship called the Imo was in a hurry that day and tugged along above the speed limit for harbor traffic. Suddenly, the two ships were in sight of each other. Each ship blew their whistles indicating right of way, eventually evasive maneuvers were impossible in the tight confines of the narrows.

As the Imo attempted to go into a full reverse, the turbulence from its one propeller torqued the ship into the Mount-Blanc. What appeared to be a minor fender bender turned deadly as sparks from the hulls separating lit spilled barrels of benzene on the ammunition carrier’s deck.

The crew of the Mount-Blanc abandoned ship, knowing a fireball worthy of hell was soon to follow. However, other ships in the harbor attempted to put the fire out, getting closer.

The fire also attracted the attention of everyone in Halifax. People stopped whatever they were doing and looked out of windows, watching the tremendous blaze.

As the crew of the Mount-Blanc hit the shore and ran for their lives, they shouted out warnings to the town. Unfortunately, the mainly English-speaking port didn’t understand French.

The Explosion

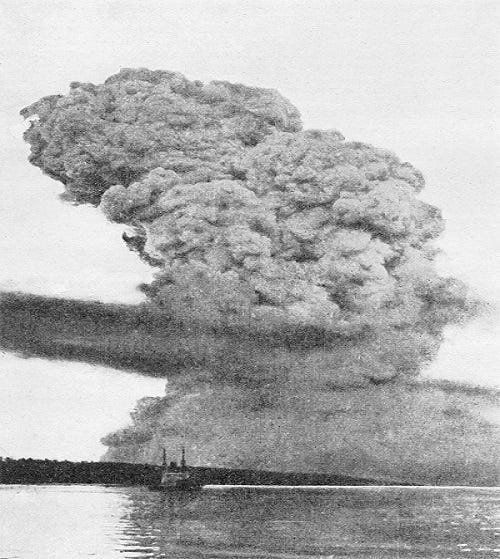

“The enormous energy released tore through the ship at 1500 meters per second. In an instant, Mont-Blanc was transformed from a ship to a three-kiloton bomb in a busy modern harbor.”

Harold Connolly was at school at the time of the blast. As he looked from his book for a second, he saw a giant fireball outside the window in the distance.

He shouted to his classmates, and shortly after a blast wave hit the school rocking the building. Connolly explained his teacher’s desk faced the window and he was peppered with glass as he watched the fire; he’d lose one of his eyes as punishment for his curiosity.

Connolly and the other children were evacuated from the school. He saw countless destroyed buildings miles from the harbor. He also had the horror of realizing many parents of his friends died during that day. He’d later lose his own father from a blood disease he developed from bad lacerations due to all the flying shrapnel.

Another child survivor, Jean Holder, described how the side of her mother’s face became paralyzed from the blast. She didn’t even notice her ear was just about torn off her face.

According to Jean, members of a team of doctors from Boston sewed her mom’s ear back together. Unfortunately, their house was torn to pieces and their boiler was destroyed — four feet of snow fell later that night to add to the misery.

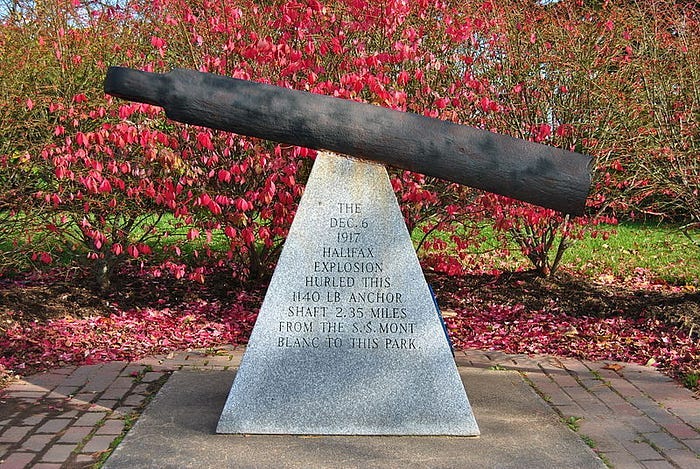

Steve Hendricks in his article explained the iron hull of the Mount Blanc vanished, turning into deadly shrapnel, flying for miles. An anchor from the ship which weighed a half ton flew about two miles.

A square mile of waterfront was totally devastated. Bodies covered in blood had their clothes literally blown off. The clock tower’s hands permanently stopped at 9:05 AM, they were left frozen in that position as a memorial to the tragedy. The article by NASA reported windows being shattered up to 50 miles away.

According to Hendricks, the casualty numbers were staggering. About 2,000 died and 5,000 were wounded. Together it accounted for 12 % of the population at the time.

Buildings everywhere were decimated (12,000 according to NASA), and countless were now homeless in the middle of a terrible winter. The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic also reports communications, rail lines, and shipping for the entire area were completely disrupted.

Make-shift morgues popped up everywhere to deal with the dead. Many alive and dead were buried in endless piles of debris everywhere undamaged eyes could see.

The Response

Halifax due to its status as a staging point for war supplies was well equipped to help itself right after the blast.

Soldiers, sailors, battle-tested nurses and doctors from Canada, England, and the U.S. flooded the area to help. In addition, hard-working locals came to aid their neighbors in need. Hendricks described an ophthalmologist working 2 days straight, removing nearly 80 damaged eyeballs.

As the disaster hit the papers, trainloads of doctors, nurses and volunteers also came in from Massachusetts. According to NASA, money came in from as far away as China. The Canadian government donated $18 million, England $5 million, and the state of Massachusetts nearly a million dollars itself. Many random people took in homeless from the disaster as well.

The article by NASA also points out countless medical innovations grew out of necessity in dealing with the disaster. Samuel Henry Prince, a survivor, also penned his doctoral thesis on the recovery. It became the first systematic study of a disaster of this type.

Tragedy And Light

If you travel into Halifax today, you’ll see the hands on their clock tower permanently stopped at 9:05 and the anchor from the Mont Blanc.

100 years after the disaster many in the world may have forgotten, but they cannot. The tragedy and destruction are never too far from their mind.

However, there is also a warm reminder of all those who ran to the disaster. Over a century later, a Christmas tree still travels all the way from Halifax to Boston.

The simple evergreen tree is a permanent reminder of the gratitude for doctors and nurses who stopped everything they were doing and got on a train on a random December day, which can never be forgotten.