The First Nuclear Reactor Was Built Under A Football Stadium In Chicago

What do the first chain reaction and Covid-19 have in common?

In 1995 a quiet suburb in Detroit had an experience the community will likely never forget. Government agents raided a neighbor’s house. Oddly, some of them were dressed like they were ready to go on a space mission.

They carefully cut up the shed in the backyard of a random suburban home, putting the pieces in sealed drums with radioactive labels on them.

While the government agency said they were the EPA there to clean up a spill, this was just a cover story. In truth they disassembled a primitive nuclear reactor. David Hahn built it in his backyard with random parts he pilfered or acquired all over.

He was only seventeen at the time.

The teenager informed local authorities on himself when a Geiger counter he made went off the charts after his device created a chain reaction.

Obviously, this is a crazy story of a dangerous experiment, performed by a rogue scientist, which put the local community at risk. Although it’s not far from the tale of the first chain reaction.

This also took place in a primitive reactor within a largely populated area. To be more specific, a football stadium in Chicago.

However, the government didn’t shut it down, but encouraged it, and rewarded the scientists that made it happen. In fact, the lead scientist is one of the most well-known names of the atomic age.

This is the tale of Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1): the first nuclear reactor.

Proving The Ability To Generate A Chain Reaction

In the middle of World War II, many are aware both the Allied and Axis powers were at work developing atomic bombs. The eventual bombs dropped get most of the attention. However, engineering the actual proof of concept had to come first.

Not just destructive power, but the ability to generate power itself: a self-replicating reaction. We know of it as a chain reaction now. Its birth took place within CP-1. According to Louise Lerner at the University of Chicago:

“A nuclear reactor is designed to split atoms. Some elements, like uranium, naturally throw off particles called neutrons as time goes by. The way a nuclear reactor works is by arranging uranium in just the right positions to encourage neutrons from uranium to hit other uranium atoms and cause them to split and throw off more neutrons, which split other atoms. This is why it’s called a chain reaction.

Many research facilities across the United States were working on this during WWII (known as the Manhattan Project). All were eventually centered at the University of Chicago.

Their base became a squash or racket ball court under the University's abandoned football stadium, Stagg Field. Strangely, the University had shut down its football team years before. The head of the Metallurgical Laboratory (Met Lab) Arthur Compton picked the area after there were too many difficulties building the device further away from Chicago.

Richard Rhodes in The Making of the Atomic Bomb, says Compton never told the president of the University or the mayor of Chicago what they were doing. According to Rhodes:

“The word meltdown had not yet entered the reactor engineer’s vocabulary — Fermi was only then inventing that specialty — but that is what Compton was risking, a small Chernobyl in the midst of a crowded city. Except that Fermi, as he knew, was a formidably competent engineer.”

Enrico Fermi, the head engineer, had explained to Compton there was a “delayed neutron response when fission occurred.” So, there was time to control it using special rods.

Fermi was so confident, when asked what he would do if things didn’t go according to plan, he replied he’d walk away “leisurely.”

Although the first reactor’s primitive appearance may not have inspired natural confidence in its safety.

The Device

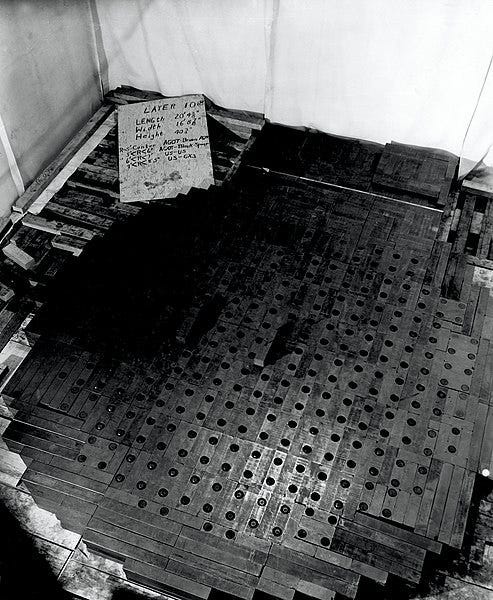

“The Chicago Pile deserved its low-tech name. It was a stack of forty thousand graphite blocks, held together in a wooden frame, twenty-five feet wide and twenty feet tall. Inside about half of the blocks were holes containing small amounts of uranium oxide; inside a few others were nuggets of refined uranium metal, the production of which was still a novel process. The Pile had few safety features.”

— Alex Wellerstein, The New Yorker

Even though the device was low tech, it took many calculations, and much trial and error to figure out the correct structure of the simple looking pile. Steve Koppes at the University of Chicago writes it was attempted about thirty times.

The final version was finished December 1, 1942, and The Atomic Heritage Foundation says it was comprised of the following material:

About eight hundred thousand pounds of graphite

Near eighty thousand pounds of uranium oxide

Over twelve thousand pounds of uranium metal

The entire structure cost close to a million dollars at the time

The Pile comprised of fifty-seven layers, as calculated by Fermi to get a value of “k” greater than one. This value represented “the effective neutron multiplication factor, which is the average number of neutrons from fission that will cause another reaction. A high enough measurement would indicate that the reaction could sustain itself.”

While it didn’t have many safety precautions, there were methods in place to control the reaction. Parts of the Pile had openings. Within these, fourteen-foot control rods made of cadmium could be slid out, causing the neutrons in the structure to go “critical.” Then, slid back in.

Rhodes mentions at least one of these rods was controlled manually, with a physicist sliding it out by inches as commanded by Fermi. However, there were three emergency measures.

One rod was activated by solenoid and slid in if “neutron intensity exceeded the chamber setting.”

Another rod was dramatically held out of the Pile via rope, which could be cut by an axe and quickly enter, like a superhero to the rescue.

A final “suicide squad” of physicists stood by with buckets of cadmium-sulfate to dump on the pile if it couldn’t be controlled.

Call it a no-frills reactor, but it was functional and the team proceeded to an all-important real world test.

The Result

The day after the Pile was complete, Fermi was confident the structure could produce the chain reaction the Manhattan Project’s scientists desired. On the morning of December 2nd, Fermi had an assistant slowly pull the manual rod out of the Pile.

In a surreal vision, a team of physicists stood above the squash court on a balcony, monitoring the “k” value on three different instruments nicknamed Pooh, Piglet, and Tigger. As the value closed towards one, a loud bang broke the silence. Rhodes says the solenoid tripped, slamming in a containment rod.

With the goal in reach, Fermi calmly sent the team to lunch. Unlike scientists close to changing the world, the team sat outside and had lunch in the Quad, like regular faculty. Koppes explains they generally discussed technical issues outside under a tree there as well.

After lunch, they went at it again. Fermi’s assistant slowly moved the rod out further as measuring tools clicked and clacked. A little after 3:30 PM, “k” became greater than one. Fermi let it go a little bit longer, and within the span of five minutes, he ordered it terminated and the rods slid in.

The team had created the first artificial chain reaction with an incredibly dangerous contraption. Plus, Fermi’s experiment only generated about half a watt of energy. Although Rhodes says the “neutron intensity” doubled every couple minutes and could have reached a million watts in ninety minutes…in the center of Chicago.

You could say it was David Hahn on an industrial scale — a time of cowboy science long past. But is it?

The Double-Edged Sword Of Science

Most of the wonders of our modern world are blessings of science. But it’s like us. The powers of the tool can either create or destroy. And as technology gets more sophisticated, so does its magnitude for both.

We also inherently believe time helps us to know better. A modern-day Fermi would never exploit such a dangerous test apparatus in the midst of a mass population. Although a lab in Wuhan may prove otherwise.

Recently the FBI and the US Department of Energy issued reports indicating the COVID-19 virus could have came from a lab leak. If so, about seven million people died due to a science experiment gone wrong. That’s over thirty two times those killed by the Manhattan Project’s atomic bombs.

Think about that for a second.

Obviously, we can’t extinguish science with a bucket of cadmium-sulfate. It must continue. But perhaps we temper our infatuation into a guarded love affair of checks and balances. Otherwise, there may be no recovery from the next blunder.

-Originally posted on Medium 1/14/23