That Time Che Guevara Tried To Make Soda

The truth behind an iconic picture and the people who live with its consequences

“Forget about Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola. Forget about them. We’ll keep bottling something that looks like them, but we don’t have the formulae. The Yankee Capitalists took them. You can keep drinking the stuff if you want, but it’s never going to taste the same.”

— Che Guevara, “Waiting For Snow In Havana” by Carlos Eire

In Carlos Eire’s book, he talks about his time as a child growing up during Cuba’s communist revolution and his eventual escape from the island. In particular he talks about a figure that many have transformed into an icon today — Che Guevara.

For Eire, this wasn’t just a figure on a poster or the face of a movement. Che “the human being” lived in a mansion right up the street.

Che also killed Eire’s relatives, stole his family’s money, and confiscated the businesses and properties of people he knew. Eire never saw the icon on the poster, he saw the real man who did terrible real-world things to make his visions come true. Eire has a poignant way of summing this all up in his book.

“Still, all of us are responsible for our own actions. Not even Fidel is exempt from all this. Nor Che, nor his chauffeurs, nor his mansion. Nor the many Cubans who soiled their pants before they were shot to death. Nor the fourteen thousand children who flew away from their parents. Nor the love and desperation that caused them to fly.”

Eire was one of the many children sent away from the island to escape the madness and possible death sentence. The family who ran Cawy also escaped without a penny in their pockets. This was the soda bottling plant Che spoke of in the beginning of the article.

Che just assumed if he got all the family’s equipment and building, he’d create the same things they did — just that easy. As Eire points out, it never happened.

The only thing Che managed to do was to make every can taste different, but all somehow managed to be undrinkable and it never got better. Eire switched to seltzer water because it was the only thing the revolutionaries couldn’t screw up.

However, Che did much more than just make sodas. He also was put in charge of Cuba’s banking system. What did he know about banking?

Not a thing, but it didn’t stop him from thinking he did or could run businesses. It makes one think of the popular psychological concept called the Dunning Kruger Effect.

Dunning-Kruger-Guevara

“Coined in 1999 by then-Cornell psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, the eponymous Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias whereby people who are incompetent at something are unable to recognize their own incompetence. And not only do they fail to recognize their incompetence, they’re also likely to feel confident that they actually are competent.”

— Mark Murphy, Forbes Magazine

In an amazing CNBC article by Michelle Caruso-Cabrera, she describes a meeting in 1980 between Fidel Castro and an American banker Bill Rhodes of Citibank.

At this time Cuba was under a terrible financial burden. They had borrowed lots of money from European and Canadian banks but couldn’t pay it back. Fidel was in such a bind; he reached out to the last person he’d ask for help — an American banker.

In the meeting set up by Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega, Fidel would make some startling admissions. First, he’d admit throwing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) out of Cuba was a big mistake.

Second, he’d say not joining the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank were poor decisions. Finally, he’d say he should have never put Che in charge of Cuba’s banking system.

“Why I ever did that, I don’t know, because obviously Che Guevara knew nothing about finance and banking. I put him in there because I guess I trusted him. But it was a mistake.”

Guevara was educated and well-traveled. However, his travels and education only reinforced his ideas. Nothing he saw ever caused him to question what he was doing.

Not even his disastrous intervention in Cuban banking or the failures when he attempted to run nationalized businesses altered his view. The cognitive bias shown by the revolutionary dovetails well with the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

“You can keep drinking the stuff if you want, but it’s never going to taste the same,” was a good way to sum up his attempts to manage things he was clueless about. If he was in charge and the organizations were in the hands of “the people” they were good — even if they didn’t work.

Dunning and Kruger also mention how the cognitively biased individual also doesn’t handle criticism well. In Cuba criticism likewise wouldn’t be tolerated and could result in your death or imprisonment.

Eventually the fears which made Eire’s family send him away from Cuba were played out in total. Work camps were set up behind barbed wire where “scum” who didn’t fit into the new Cuban society were sent.

These camps were made up of religious groups, gays, vagrants, and those disaffected. “Work will make you men” was posted in signs around the camps. However, most don’t know this; the Che they know is the one in the iconic picture.

Making Money Off A Marxist Icon

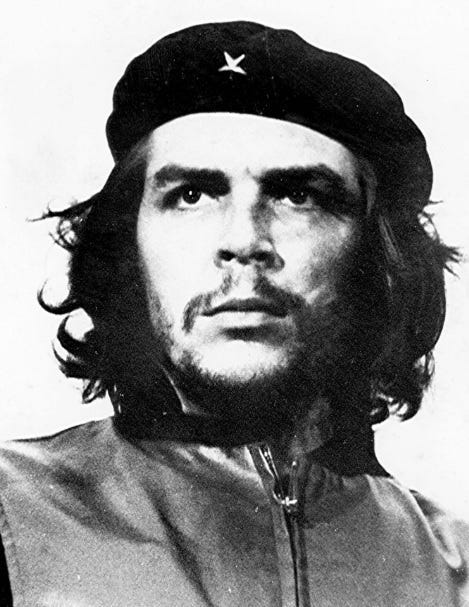

I’m sure you’ve seen the photo above many times. However, how much do you know about its capture and creation?

The picture itself was taken by Alberto Korda at a funeral according to Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo’s article in the Smithsonian. The funeral was in honor of over a hundred who died unloading a ship in Havana Harbor.

The ship was carrying munitions Cuba purchased from Belgium and surreptitiously brought to the island. To hide the weapons from prying eyes, the revolutionaries had regular dock workers unload the ship without explaining what the cargo was.

At some point some of the weapons exploded. The reason for the explosion wasn’t explained — possibly on purpose.

The funeral turned into a capitalism bashing fest hosted by Fidel Castro, who accused the United States of causing the explosion. His only evidence of this was his word, and it was all that mattered.

It couldn’t possibly have been caused by dock workers who didn’t realize they were unloading a dangerous cargo of explosives. Fidel’s words incited the crowd and one of his lieutenants, Che.

Korda happened to be at the funeral and snapped the picture of Guevara at a given moment of angered contemplation. The photographer had to crop out trees and another man’s face to focus on Che and his expression. Korda tried to get a local newspaper to publish the picture, but it was declined. So, he hung the picture on his wall and there it sat.

About seven years later an Italian businessman met with Korda. He was part of a think tank trying to promote ideas of the Cuban Revolution. He asked Korda if he had any pictures of Che. Obviously, he pointed to the picture on the wall. Korda gave the businessman copies, possibly because it was illegal to charge for the prints in Cuba.

The wealthy businessman Giangiacomo Feltrinelli started selling the prints after Che’s death, giving no credit to Korda. Feltrinelli also published Che’s diary after it was given to him by Fidel Castro — putting Korda’s picture on the cover. Korda eventually fought in a London court and did have some legal claims addressed before his death, receiving $50,000 for the iconic photo.

Don’t “Forget” About The Soda

So, what happened to Che’s attempts at soda? There’s not much to show for it. According to Lazo’s article in Smithsonian magazine, Che bailed out in 1965 to spread the revolution to other areas since it had sold so well in Cuba. There’s that Dunning Kruger Effect again. Although, the story of Cawy didn’t end after nationalization.

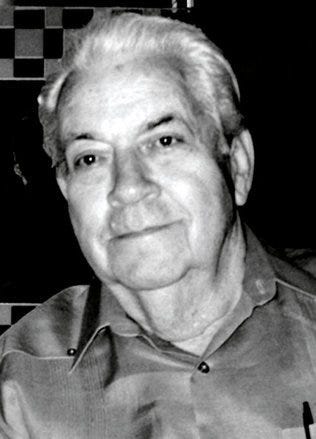

Alberto de la Cruz on his Babalú Blog explains Vincent Cossio, the founder of Cawy, landed in Miami without a penny in his pocket in 1962. He built the soda company again in a new land. In addition to the old favorites, he created new flavors, and the company is still going strong. He didn’t need the plant and equipment Che confiscated — just the know-how and the desire to make something people actually wanted.

Vincent died in 2011 at the ripe old age of eighty-three. However, Cawy still lives — poetically outliving both Che and Fidel. Many may look to that iconic picture of Che as inspirational. However, the true inspirations are Vincent Cossio and Carlos Eire. They were chased from their homes, arriving in a foreign land with nothing, only to become successful through their own effort and sweat. Now, that’s inspirational.

-Originally posted on Medium 8/5/20

I once met a cousin of Cuban musician Silvio Rodríguez, then living in Canada, and he shared with me the - perhaps apocryphal - anecdote that during Che's time as Minister of Industries, he was informed that miners were experiencing health issues because they were unable to urinate due to the extreme heat and dehydration of working in deep mining shafts. Che's solution to the miners' urinary constipation? He had a now-nationalized Cuban beer factory send them... free beer.