Secret Massive Pipelines Across The Ocean Supported The D-Day Landing

The biggest invasion force in history was supported by an even bigger supply system

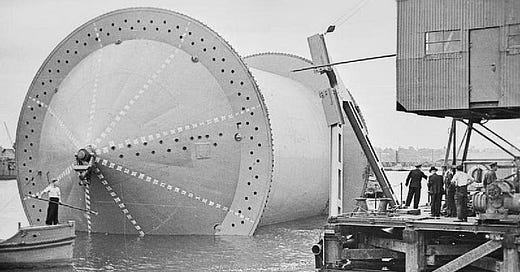

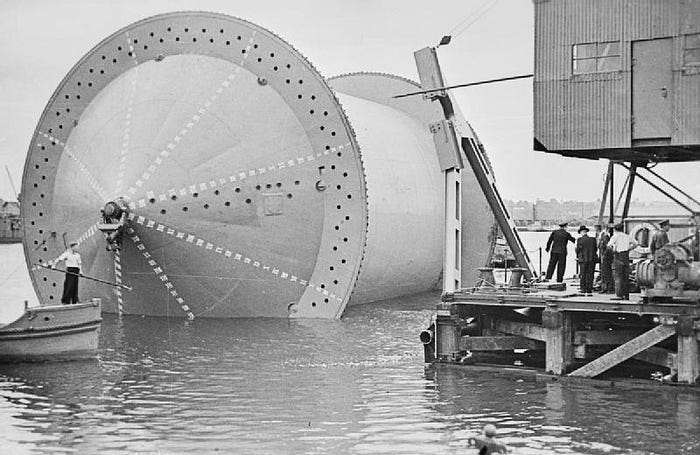

Conundrum For Laying Pipeline — Imperial War Museum Via Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]

“Napoleon’s dictum should be revised to fit the modern army, it moves not on its stomach but on gasoline.”

— General Omar Bradley, quoted by Arnold Krammer. “Operation PLUTO: A Wartime Partnership for Petroleum.”

Amazon is usually thought of as a technology company, but this isn’t exactly the case. It’s more of a logistics company. To get those packages to you quickly, it owns a combined force of 70,000 semi-trucks and vans, along with an air force of 70 planes. They even have their own air hub in Kentucky.

If you think about it, an army is very similar. We may see it as a fighting force, but it usually spends more time handling logistics than shooting.

For instance, on D-Day, not only did the Allies have to fight the Germans on shore, but transport over 300,000 troops, 50,000 vehicles, and 100,000 tons of supplies. Talk about a logistical nightmare.

But here’s another thought for you.

How do you fuel all these vehicles and equipment continuously? Tankers from England? This puts your fuel supply at risk to submarine or air attack and the forces of nature. Plus, imagine how many boats would be required to fuel this massive force every day.

The Allies had another plan — a secret mission worthy of a James Bond movie. They’d use PLUTO, not the planet, but the Pipeline Under The Ocean.

Hartley Can Make The Impossible Possible

Arnold Krammer in his scholarly article notes the Allies had an odd problem with any upcoming invasion of Europe. How do you fuel it? The British War Office estimated about two-thirds of the total supplies would be oil or oil-related.

This would tie up lots of resources, plus the shipping route was notoriously treacherous. Lord Louis Mountbatten, Britain’s Chief of Combined Operations, thought of a novel idea: let’s put a pipeline across the English Channel. He approached the Secretary of Petroleum, who put it before their experts.

The answer was a resounding “no.” It would require them to lay six-inch spans of pipe across a notoriously rough sea, in a war zone, over the span of fifty or sixty miles. It was impossible, forget about it.

By an odd coincidence, Clifford Hartley happened to be visiting the Petroleum Warfare Department and heard their prognosis. He was the head engineer for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and had lots of experience with pipelines. He thought it was totally possible.

In his article for the Journal of the Royal Society, Hartley personally writes about his experiences with a three-inch pipeline in Iran before the war that could move 100,000 gallons a day. It used high pressures of 1500 PSI and moved the fuel up hills.

Hartley realized laying the pipe would be difficult. You were under tight schedules due to the tides and weather, but he had a plan for that.

“I then thought of submarine cable practice, and suggested that it might be possible to make a pipe in one continuous length…without the cores and insulation, but with strong armor to enable the lead sheath to withstand high internal pressure, and that it might be laid right across without stopping, from a cable-laying ship.”

Laying the pipe this way also gave you another added benefit — just lay another pipe if you need more fuel flow. As for building this magical pipe, Hartley had an idea about that too.

Building Something Truly Unique

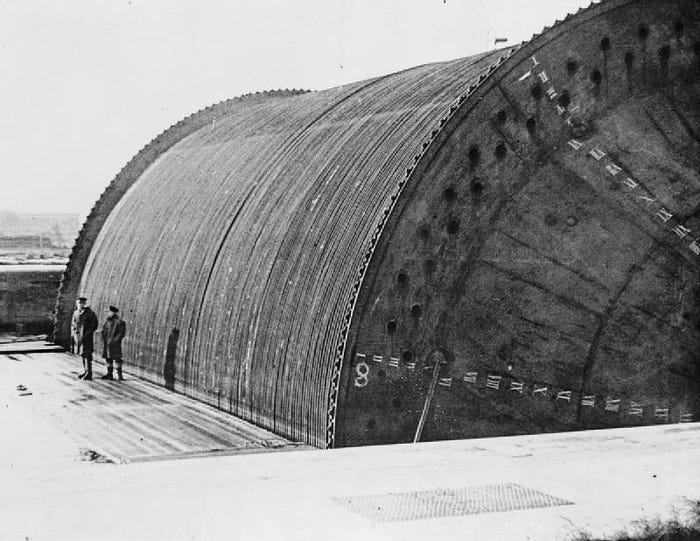

Hais Pipe (Hartley-Anglo-Iranian-Siemens)

Hartley approached the chairman of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, Sir William Fraser, who liked the idea. He also happened to be the petroleum advisor to the War Office. Fraser connected with the director of Siemens Brothers, who also got onboard.

Siemens took the existing underwater cable design and worked with the UK’s National Physical Laboratory to modify it to transfer fuels.

The two-inch pipe was made from lead. They surrounded this with asphalt and a paper with resin. This layer was then wrapped with steel tape. Another layer of asphalt and jute tape after this. Finally a layer of fifty galvanized steel wires went around the tube and was covered by camouflaged canvas.

Hais Pipe — Picture By Geni at English Wikipedia Via Wikimedia Commons

In May of 1942, a 120-yard test length was laid across the Medway River in Southern England by a Post Office ship. After a failure, more layers of steel tape were added. Stunningly, the pipeline worked. Another successful test was carried out in June.

A few months later a full-scale trial of the PLUTO project was rehearsed. A thirty-mile length of pipe was laid across the Bristol Channel in rough water. The test was a stunning success. The pipe originally was tested with a pressure of 750 PSI passing through it, which they doubled soon after. So, the line was moving 250,000 liters a day.

The group was so pleased with the results, they decided to boost the pipe up to three inches. The Navy procured a couple merchant ships which they converted into pipe-layers. Each could manage a hundred miles of the three inch pipe.

Hamel Pipe (Hammick and Ellis)

Due to the lack of lead, the military needed a backup pipe. Bernard Ellis and H. A. Hammick, the head engineers of the Burmah Oil Company and the Iraq Petroleum Company, thought mild steel was a good option. So, they created a three-and-a-half inch pipe, but it wasn’t flexible.

This proved to be a conundrum.

Conundrum Loaded With Hamel Pipe — Imperial War Museum Via Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]

Although they couldn’t lay via cable ship, they produced another idea. They built steel towable drums forty-feet in diameter, which could be used to roll out the steel “Hamel” pipe. Showing off their best pre-Monty Python humor, they called them Conundrums (add your best rim-shot here) or “Conuns” for short.

Hartley notes each of these Conuns could carry seventy miles of pipe and weighed about as much as a destroyer.

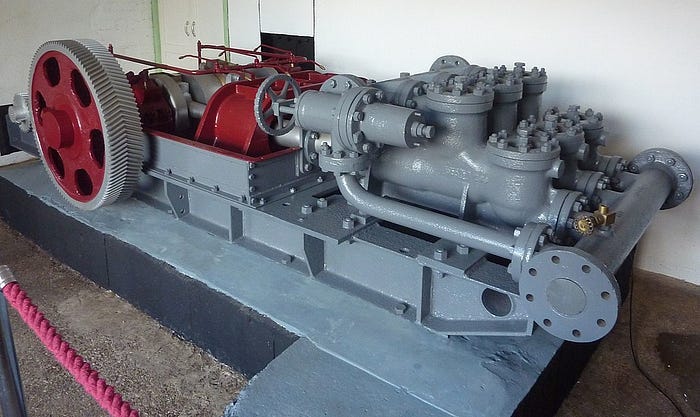

Pump Houses

Operation PLUTO Pump On Isle Of Wright — Picture By MarkS Via Wikimedia Commons

Obviously, you need pumps to move the fuel through the lines, and places to house the pumps. Stationary structures were easy targets for air attack or sabotage. Here, Hartley notes the “expensive and irksome” effort to hide these stations.

Hartley says a Camouflage Officer was in charge. These locations were set up at night and disguised as houses, gravel pits, garages, and even an ice cream factory. These stations used a mixture of diesel driven reciprocating pumps and electrically driven centrifugal pumps.

Originally Brown’s Ice Cream Factory (PLUTO Pump Station) — Picture By John D Ryan Via Wikimedia Commons

PLUTO In Action

The pipeline had two major iterations. The first code named “Bambi” was a relative failure. Only two of each line was laid, with significant trouble setting them and continuous failures. However, a second attempt was tried after lessons were learned from the first.

The second operation “Dumbo” proved to be much more successful. Although much of the Allies fuel came via tanker, the Germans still attacked ports. A backup method was necessary to get fuel. So, a second pipeline was planned from Dungeness across the English Channel.

PLUTO Pipeline Map (Left) Bambi, (Right) Dumbo — Picture By Library Of Congress Via Wikimedia Commons

According to Krammer, a Hais pipe was laid and began pumping October of 1944. By December, a total of seventeen mixed Hais and Hamel pipelines were going, and by 1945 moving 4600 tons a day of fuel.

Our World Revolves With Unseen Infrastructure

Many years ago, I got a sudden surprise. A world I’d never thought of opened to me by chance. A construction company talked to me about a portable instantaneous hot water heater they use to heat divers’ suits in the wintertime. This company does underwater construction.

An unbelievable amount of infrastructure exists underneath the ocean to keep our society going, which most know nothing about. But it’s not only here. While we believe we’re in a new tech age, we still drive on roads, land in airports, and live in buildings that get water pumped in and out of them.

Internet Cable Map (2007) — Via Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]

All this is done with steel, concrete, and mechanical devices. Even the internet you’re using now to read this article is being “pumped” through a vast network of underwater cables, which must be laid and maintained by technicians via ships.

The map above is actually old. The modern map dwarfs this and looks like a silly string party got way out of control.

All this infrastructure requires people willing to get dirty to make it all happen. In an age where society pushes us to be knowledge workers and to learn to code, none of this happens without people willing to do the heavy lifting.

It was the same on D-Day and hasn’t changed today. While we celebrate the men who fought and suffered, a large support service was supplying them. Without them, the armies would have never left the beaches.

Similarly, tech and knowledge workers wouldn’t even be able to turn their computer on or access the internet without the cables, concrete, and construction workers creating and maintaining this new age of tech.

-Originally Posted On Medium 1/13/22