Riches May Be In Niches, But Broad Connections Change The World

Consilience: a way to connect the trees of wisdom

As a kid, you get your first glimpse of adulthood in the form of a question every child eventually gets asked. What will you be when you grow up? It’s the adult world’s way of getting youth to whittle down possibilities.

Your questioner expects you to say one thing, or maybe two at most.

If a five-year-old rattles off ten different possibilities, they’re not taken seriously. Keep doing this at sixteen, and you’ll get a lecture from annoyed parents. Unfortunately for me, I continued doing this as a freshman in college, much to the disappointment of my student advisors.

I didn’t pick a major until the last possible minute because of my wide-ranging interest in…everything. College wants you to specialize. In fact, the entire world wants you to pick a lane and stay in it.

It’s an effective strategy but comes at the cost of building a wall between your niche and other interesting lanes. Biologist E.O. Wilson saw this wall, too, between science and humanities, and thought it was limiting. In a lecture at Harvard, he stated:

“The nub of the problem…vexing a great deal of human thought, is the general belief that a fault line exists between the natural sciences on the one side, and the humanities and humanistic social sciences on the other. (between the scientific and literary cultures).”

Wilson claimed this fault line shouldn’t exist, calling the separation imaginary. He coined, or revived, a word to explain his vision: consilience. It represents a method for connecting the various trees of knowledge into a unique whole (like Henriques’s diagram above).

Wilson defined the term as: “the interlocking of cause-and-effect explanations across different disciplines, as, for example, between physics and chemistry and biology, and more controversially, of course, biology and the social sciences.”

The biologist saw this idea as common sense, since “the brain, mind, and culture are composed of material entities and processes,” that “do not exist in an astral plane above and outside the tangible world.”

In other words, tear down walls and connect niches. Scientists, philosophers, historians, engineers, and reps from all disciplines should intermingle and learn from each other. The results would open countless new doors.

While novel, consilience isn’t new. Wilson just gave a word to something that’s always been with us and powered brilliant figures of many ages, giving them special abilities to see what isn’t always clear.

It enables some to predict the future (foresight).

It renders others immune to the blindness that infects the masses during their own time (clear sight).

Consilient thinking creates paths for creators to build truly novel things (unique sight).

It may even be the one thing that protects us from artificial intelligence replacing humanity (irreplaceable sight).

Let’s begin with foresight.

Foxes, Hedgehogs, And Superforecasters

Author and political psychologist Philip E. Tetlock has always been interested in prediction and the ability of humans to judge. Between 1984 and 2003, he started a series of prediction tournaments. The participants were experts from government, journalism, and a variety of fields with different political persuasions.

Over the study, they submitted about 28,000 predictions, and Tetlock discovered surprising results.

The group, at best, did only slightly better than chance but was often worse.

The highest-profile experts were the worst of all.

The psychologist also divided the participants into foxes and hedgehogs based on a tale by the ancient Greek poet Archilochus and an essay by political theorist Isiah Berlin. Hedgehogs had deep knowledge about one thing, while foxes knew a little about many things.

The foxes performed better, especially as the predictions stretched further towards the future. Tetlock’s experiments stoked the interest of the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), within the U.S. intelligence community. They, in turn, started their own prediction contest.

It invited tens of thousands of experts. So, Tetlock started his own prediction group called the Good Judgement Project (GJP), loading it with a preselected team of foxes. They won. During the contest, GJP showed they were 30% more accurate than intelligence officials with access to classified information.

Tetlock also discovered what he called “superforecasters.” These were individuals that consistently showed ability to predict future events. Part of what made them so good was their foxy ability to gather information from multiple domains.

But, beyond the future, consilient thinking also helps with the present and clear sight.

Removing The Cataracts That Blind You In Your Own Age

“Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself. If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun.”

— C.S. Lewis, Learning In War Time

In 1939, C.S. Lewis and the faculty at Oxford faced an interesting dilemma. The world was on the verge of war. Many wondered if the college should close during this national emergency.

Amid the naval gazing and handwringing, C.S. Lewis gave a quick and clear answer: hell no!

In his speech Learning In War Time, he details countless historic examples of how humanity continued the pursuit of knowledge and aesthetic beauty despite the chaos the world chose to throw at them in their time.

It was easy for Lewis to see because he spent so much time studying various disciplines from the humanities, history, poetry, and science. He states:

“A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village.”

Likewise, a scholar who’s “lived in many times,” is to a “degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.”

So, the study of these various disciplines wasn’t petty nonsense; it was time travel and a wider view of the world around you. This enabled the viewer to see beyond the nearest trouble spot. It also clears your vision, blinded by the day’s popular narrative.

But beyond clearing your vision, a consilient approach also enables you to envision novel things with unique sight.

Seeing Beyond The Walls That Close Us In

When I first started writing, I copied what other famous writers were doing. Most take this approach in any new endeavor. Eventually, you need to shed that skin and grow something uniquely of your own.

Blogger Henrik Karlsson says your contradictions are this unique skin. In Advice For A Friend Who Wants To Start A Blog he says:

“Your contradictions are an asset. You’re a lover of classical English architecture and you’re also a dirty little punk — expressing both at the same time is more interesting than sharing just cute pictures of English gardens or just wild trashy stuff. The more you incorporate everything that you love and that comes easily for you (your interests, your sense of humor, your grammatical tics, etc.), the more your style emerges.”

This contradiction could also be a mishmash between various things you’re interested in that turns into something truly special. History is full of these instances.

In Japan’s feudal age, a samurai named Miyamoto Musashi became famous in his time, winning sixty-two consecutive duels. He also loved art too, creating beautiful pieces that still awe viewers today. But the samurai gained immortality with a pen.

He took all the wisdom from his varied interests and put them together in a legendary guide on strategy and life, disguised as a manual about sword fighting called The Book of Five Rings.

Mary Shelley combined a love of literature and writing with an interest in a new field of science called electrophysiology. Italian scientist Luigi Galvani had proven sending electric current through nerves could cause limbs to shake. Later, this method was used to make a cadaver move.

Shelly turned these contradictions into Frankenstein.

C.S. Lewis combined his scholarship in medieval history, spirituality, and interest in politics into The Lion, Witch, and the Wardrobe series. But the definition of consilient thinking is Leonardo Da Vinci.

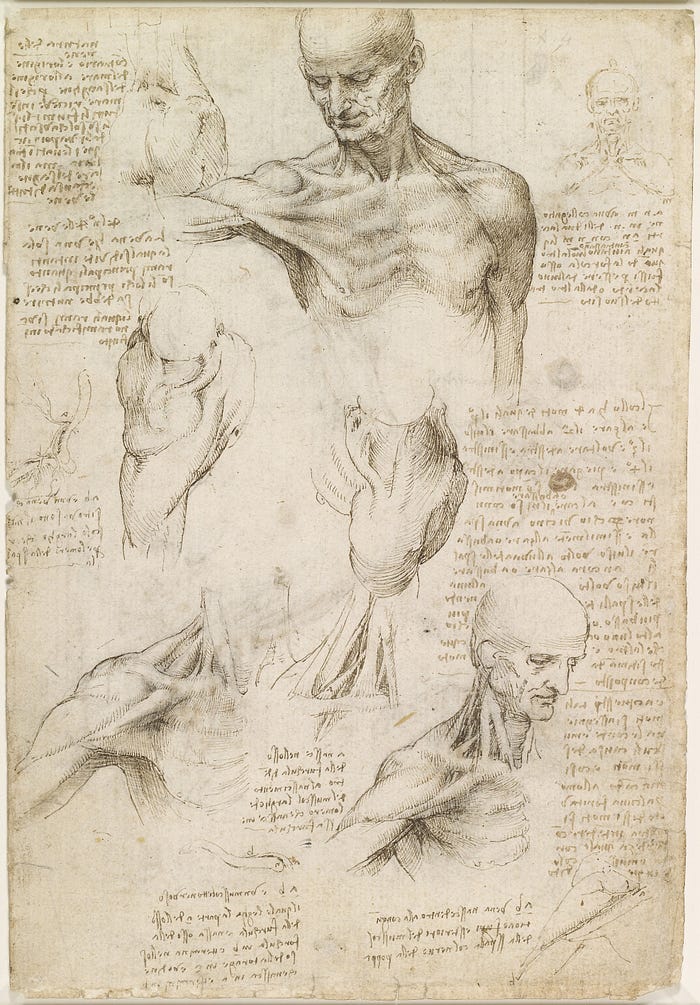

While many consider Da Vinci an artist, he did much more. It’s thought he wrote over twenty-eight thousand pages of notes on the various subjects he was interested in: biology, art, engineering, anatomy, mathematics, flight, and science. Text and art are combined in these codices.

In Ken Burns’s documentary Leonardo da Vinci, the filmmaker reveals Da Vinci considered nature his teacher. His skill in replicating the human form came from a detailed study of it. Da Vinci dissected at least thirty bodies.

During one of these dissections on an older man, Da Vinci noted the walls of his arteries had become thick, which would obstruct the movement of blood. He knew this from his study of river engineering. When a river becomes silted, it slows the flow of water, like clogged arteries would do for blood.

This was the first diagnosis of coronary atherosclerosis (or buildup of plaque in the arteries). Da Vinci did this in the 1500s.

His knowledge of engineering also enabled him to figure the heart had four chambers, when most thought it had two. Da Vinci even made sketches of a cow heart pumping blood so detailed, a heart surgeon from the UK used them in 2005 to develop a new method to repair heart valves.

In his many studies, Da Vinci noted seeing patterns repeated throughout the natural features of the earth, the animals on it, within our bodies (lungs and arteries), and the branches of trees.

About five hundred years later, mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot used the power of IBM computers to create a branch of mathematics called fractal geometry. It found repeating patterns everywhere in nature, but Da Vinci didn’t need a computer to know this — just consilient thinking.

While the consilience of the titans above shows unique vision, it may also save us from being replaced by artificial intelligence.

What Large Language Models Can’t Do, And What We Can

The current version of AI has a logic problem. In his article in Quant Magazine, Anil Ananthaswamy explains the current versions of LLMs struggle with certain logic problems. These riddles, called Einstein’s puzzles, require a solution generated by figuring out smaller problems.

LLMs are designed to guess the next word in sequence, which they do well. But figuring out multilevel problems like the ones above requires fixes and stretch their limits. Unfortunately, life is a nonstop Einstein puzzle.

This is the final gift of consilience. What better to handle the puzzle that life continually represents, but consilient thinking. It gives us foresight, clear sight, unique sight, and finally irreplaceable sight an LLM can’t duplicate.

Consilience’s gifts have also been demonstrated in the real world by E.O. Wilson, Gregg Henriques, Phillip E. Tetlock, Henrik Karlsson, C.S. Lewis, Miyamoto Musashi, Mary Shelley, and Leonardo Da Vinci.

With all this in mind, I want to rephrase that childhood question one more time. Now that you’re an adult, what do you want to be?

My suggestion: pick more than one thing, be a fox, don’t be afraid of contradictions, and combine your choices in a unique way only you can. Riches may be in the niches, but broad connections change the world.

-Originally posted on Medium 2/11/25, if you’d like to learn more about this topic, I’d recommend the story I wrote about Da Vinci below, he’s a living example of consilience in action.