How Technology Replaced Arrows And Silenced Our Universal Language

An emperor, an author, and a storyteller give us lessons on connection in our time

Sometimes it’s hard to understand how quickly things change when the world is morphing around you. It takes perspective to make this clear, and the past usually gives me this perspective.

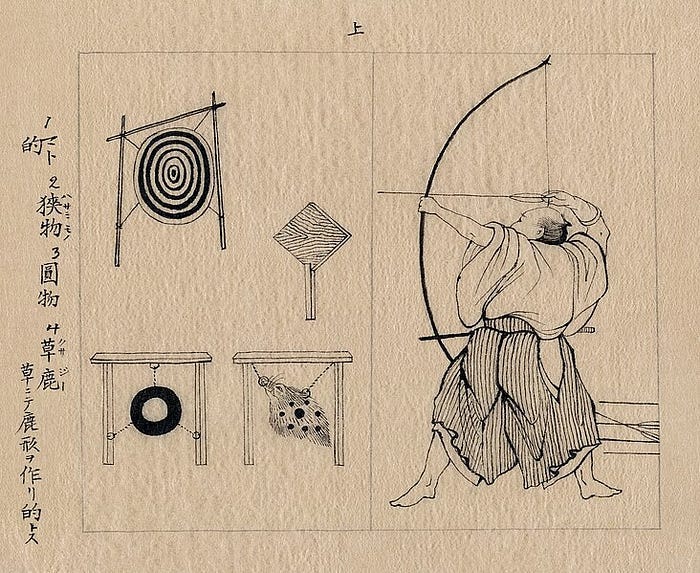

The first archeological evidence of a bow and arrow was found in South Africa, and dates to about 60,000 years ago. Over time, this technology spread around the world. For the most part, it didn’t change much.

Bows and arrows looked and functioned the same, so eventually, they became universal tools for countless people. In fact, they were so pervasive, cultures across the world used them as moral teaching devices to pass on important lessons to the next generations.

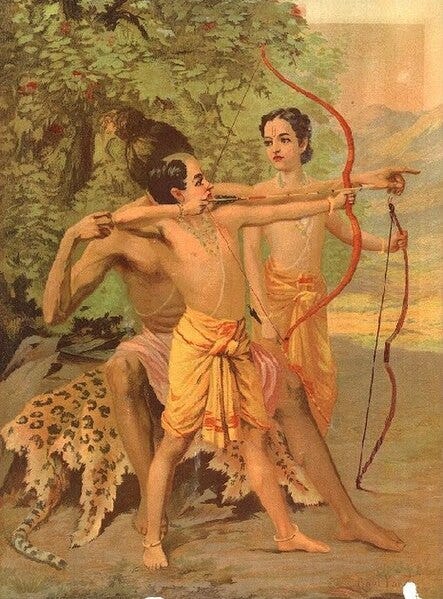

In ancient India, the ends of the bow represented humanity’s heavenly and earthly nature. The string that connects the two must have the right tension, or it can’t function effectively.

The Lakota tribe used the bow and arrow to explain the relationship between the masculine (men) and feminine (women). Nothing gets done without a harmonious relationship between the two.

Early Christians used the Greek word hamartia, an archery term, to refer to sin. When you sin, you miss the mark.

Ancient Greek philosophers used archery to explain a concept of Stoicism. Happiness isn’t dependent on whether you hit the mark. The important thing is shooting well, but an arrow’s path can be out of your control.

In Zen In The Art Of Archery, Eugen Herrigel discusses how Zen Buddhism teachers use the skill of archery to explain their theology. Herrigel describes archery as “spiritual exercises…whose aim consists in hitting a spiritual goal so that fundamentally the marksman aims at himself and may even succeed in hitting himself.”

Not only was the bow a universal tool, but it also built a common language throughout various cultures for thousands upon thousands of years. Then, it disappeared in the span of a few hundred years. In a way, this is a microcosm for what we’re experiencing today with technology.

Years ago, professions and cultures passed down from great grandparents to great grandchildren, but no longer. Some might say this is a good thing. Although something gets lost when that continuity goes away — a common language and understanding between generations fades. Important lessons get lost with it.

This is only getting faster too. As technology changes the world around us at blinding speed, and things transform endlessly, can we even have a universal language like we had in the past? Also, do we need one?

We’ll focus on the second question first.

Growing An Empire And People With A Common Story

In 27 BC, after years of civil war, Augustus (Octavian) became the first emperor of the Roman Empire. His first goal was to restore stability. Augustus gave the senate back some nominal power and went to pains to demonstrate he wasn’t a hereditary monarch, although he was.

He gave himself the title of Princeps Civitatis, or first citizen. Augustus also met with a friend and great poet, Virgil. Some thought this was odd. Why would a poet be so important?

John Lewis Gaddis, Professor of Military and Naval History at Yale, says Virgil created a glue that held this new version of Rome together. The young empire needed a story to create a common language, so Augustus paid Virgil to write it.

In his book, On Grand Strategy, Gaddis says:

“Rome had no Homer, so the Princeps provided one. The Aeneid, unlike the Iliad and the Odyssey, is a commissioned work. Augustus encouraged its composition, subsidized its author, and saved the manuscript from the flames when the dissatisfied Virgil, on his death bed, asked to have it burned.”

To the Romans, the Aeneid became a rock of their civilization, much like Homer’s works were for the Greeks. In our modern times, C.S. Lewis agrees that similar cultural glue is necessary for a functional society.

In his book The Abolition of Man, Lewis explains that humans act through their heads, bellies, and chests.

The head represents higher thought and logic.

The belly is base nature and animal desires — hunger, anger, lust, and simple instinct.

The chest mediates between the two, combining emotion and logic.

All head means you’re logical but cold and detached. All belly means you’re nothing more than a “trousered ape” and no different from an animal. So, the chest is an important tool that turns us into functional humans.

But using your chest isn’t intuitive; it can only be learned through values passed on by others. Lewis compared it to “old birds teaching young birds to fly.” He says each world culture has its own set of morals and universal language to teach proper chest use.

He calls these universal morals and language “the Tao.” Lewis also says modern society has diminished this language’s importance, turning everything into a subjective set of values everyone makes up on their own. Technology adds to this, quickly changing the familiar roots of society.

This leaves a major problem. Without a common language, how can you learn to use your chest? Lewis sums this up in one quote:

“We make men without chests and expect from them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

Since Lewis and Augustus have established the importance of a universal language, we’ll move to our first question. In this technological state of constant change, can we still have one today?

The Fables Hidden Below The Surface

Sometime in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BC, a slave compiled a collection of stories about animals that taught moral lessons. Or so the story goes. The magical storyteller’s name was Aesop, and his collection of tales became known as Aesop’s Fables.

These stories passed through Greece, to Rome, the Middle Ages, and eventually to the Renaissance. People of all these times used the stories to educate their children and teach valuable lessons. You’ve also used them yourself without ever knowing it. Do any of the following sound familiar?

Laugh and the world laughs with you (Bald Huntsman).

Things are not always what they seem (Bee-Keeper and the Bees).

Deeds speak louder than words (Boasting Traveler).

Necessity is the mother of invention (Crow and the Water Jug).

Slow and steady can win the race (Hare and the Tortoise).

Heaven helps those who help themselves (Hercules and the Wagoner).

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder (Jupiter and the Monkey).

If we really want something done, it is best to do it ourselves (Lark and the Farmer).

United we stand, divided we fall (Man and his Sons).

To each his own (Town or City Mouse and the Country Mouse).

Aesop’s Fables also include The Goose That Laid The Golden Eggs, where we learn not to be short-sighted with valuable resources. The Ant and the Grasshopper teaches us to work hard and plan for the future. Where The Fox and the Grapes, gives us the phrase “sour grapes,” and the idea behind it.

While technology may have put the bow in its grave, and silenced much of our universal language, Aesop could tell you the Tao isn’t finished just yet. Since heaven helps those who help themselves, we’ll need to do some work to keep a universal language going.

Keeping A Common Language While A Tower Collapses

I recently saw an amazing technology. A company called Time Kettle created these ear buds that instantly translate from another language into your own. It creates near seamless two-way conversations without barriers.

This gives us endless possibilities.

I couldn’t help thinking about the story of the Tower of Babel, though. In this version, technology synchronizes our spoken words while destroying our tower, which is made of the common language of tradition and ethics that teach us how to use our chests.

As our world changes and we lose all the anchors the Tao provides, we’ll need to take Augustus-like action to preserve our own common tongue. Otherwise, we’ll be lost to whatever direction an algorithm points us.

But we don’t need to buy or create this universal language like Augustus did. It’s already there, just waiting for us to revive it.

I’ve often mentioned the power of classics. By this, I mean not just works of literature but ideas that have been around for more than fifty years, stretching to thousands of years.

They’re tools that connect us to timeless and immortal ideas, holding back the battering winds from TikTok, or whatever tech contaminant of the minute that’s sucking away our mental horsepower.

As we’re flooded with constant new content, it’ll be up to us to temper this with classics to save our sanity. Not only this, but we’ll need to share these things. Each of us can be the Aesop of our own time.

The Tao is useless unless it’s shared, and that’s where we come in.

Technology may have buried the bow, but our universal language is only silent unless we stop speaking it. So, speak it loudly. Share it with pride, and make sure it continues to echo long after we’re gone.

-Originally posted on Medium 5/10/25