How Petra Supported 30,000 People On Four Inches Of Annual Rain

The Nabataeans created a kingdom of water in the desert

There are some images you can always remember. I vaguely recall watching Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as a kid, but the plot or actors weren’t the memorable part. A manmade landmark stole the show.

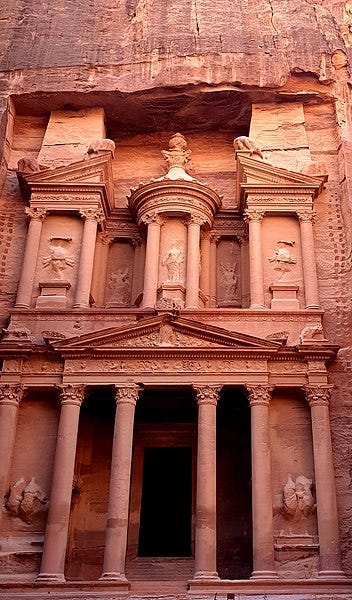

Harrison Ford and Sean Connery move through a gorge that blocks their peripheral view ahead of them. As the camera pans forward, a magnificent building appears, which you can see above. While Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were involved, it wasn’t special effects.

This was part of the ancient city of Petra in present-day Jordan. Realizing this wasn’t a movie prop was a jaw-dropping moment for me.

People had carved this mixture of art and living space out of stone. The sheer grandeur of the visual has the power to create awe in the viewer, which is the point of the display. But it overshadows something even greater.

Within the gorge entrance to Petra (called the Siq), small channels are cut into the solid walls. They hold a secret in plain sight. It explains how the builders of Petra, the Nabataeans, created a city in the middle of the desert that supported tens of thousands despite sparse rainfall.

While Petra’s stone buildings are impressive, its water management system created the opportunity for life on a grand scale in an arid world where nothing green should exist. Not only did the Nabataeans have enough water to drink, but they also turned its abundance into works of propaganda for the ancient world.

However, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Before we can get to Petra’s water management, first, we must understand why you’d build a city in such an inhospitable place.

Nabataeans: From Delivery Agents To Rest Stop Management

Not much is known about the Nabataeans until 312 BC, when they resisted an invasion attempt by a Macedonian king after Alexander. The attack took place at their mountain stronghold of Petra. So, some form of the city existed at this time and must have been formidable.

In the documentary series Civilizations Legacy: From the Nabataeans to the Jordan, Martha Joukowski, an archeologist from Brown University, says the Nabataeans were master caravan travelers.

They handled goods from China, the Kingdom of Sheba, Aqaba, and Palmyra. These items included silk, cotton, horses, copper, iron, dyes, pearls, spices, incense, and people (willing and unwilling travelers). However, these mobile merchants established a settlement at Petra for the following reasons.

Permanent shelters provided protection and a place to store goods.

Safety could also be offered to other traders for a fee.

Joukowski says a strategically placed settlement like Petra allowed for the control of caravan traffic from the Saudi Arabian peninsula into Syria, across the Sinai, or even to the port of Gaza.

So, the Nabataeans went from busy delivery drivers to running the most exclusive rest stop before the inhospitable desert. It paid off.

By the first century BC—and for about two hundred years after—the kingdom went through a building boom until Rome annexed it in 106AD. Many of the incredible structures Petra is known for were carved out of sandstone during this time, and the city reached a population of 30,000. However, this required more than money; hydraulic engineering skills were necessary.

The Power And Politics Of Water

In her Ted Talk, Archeologist Dr. Leigh-Ann Bedal from Penn State University says Petra today gets about as much rain as it did at its apex—about a hundred millimeters a year (or roughly four inches). Yet the city had enough drinking water for its population and lavish displays.

Dr. Bedal says the Nabataeans leveraged four natural springs in the surrounding mountains to capture rainwater. However, the springs weren’t close—they were all miles away and required an aqueduct to bring the water into the city.

However, where Romans raised their aqueducts, the Nabataeans kept theirs close to the ground. This took the form of over fifteen miles worth of carved channels within the rocks surrounding Petra. They also created many cisterns to hold captured water.

Oddly, dams also had to be made to divert occasional flash floods in the rare instance substantial rain did occur. Dr. Bedal says the Nabataeans’ efforts to manage water were so successful that they used them as propaganda.

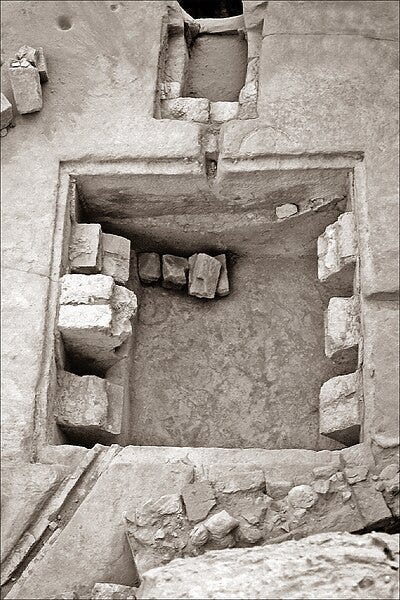

On a large terrace once considered a market, Dr. Bedal and other archeologists discovered it was the site of a garden and pool.

This wasn’t a little pond either. This “grand pool” was about 150 feet long, half that distance wide, and about eight feet deep. It also had an island in the center, with a stone pavilion or building on top. Dr. Bedal thinks elites used the area for banquets or meetings. But this wasn’t all.

Channels of water exited and entered from all different angles, and the entire terrace surrounding the pool was a garden. The archeological team found evidence of groves of palm trees planted there.

According to Dr. Bedal:

“The garden itself was a type of visual propaganda, a political statement about the conspicuous consumption of what was most precious.”

The display put the Nabataeans on equal footing with the Hellenistic kingdoms in the area. However, the hidden hydroengineering prowess to make this happen surpassed Petra’s neighbors.

A wonder of ancient hydraulic engineering

“While the Nabataean hydraulics knowledge base is not available from surviving literature from that period…As many of their solutions exhibit modern approaches, one can belatedly attribute to the Nabataeans their role as creators of a previously unreported hydraulic science.”

— Charles Ortloff, Three Hydraulic Engineering Masterpieces at 100 BC- AD 300 Nabataean Petra (Jordan)

Charles Ortloff, a research associate in anthropology at the University of Chicago, studies computational fluid dynamics (CFD). This computer-aided design technique uses data analysis to predict how fluids and gases will move. Ortloff brought this skill to Petra.

He found that the Nabataeans originally used rock-carved channels to carry water but eventually started using terracotta pipelines. While this seems like an improvement, it also adds problems.

Unlike modern pipes, the types available in Petra’s heyday weren’t threaded to fit together.

They had socketed joints to connect them but were probably sealed with hydraulic cement.

This made the joints a weak spot and made them unable to handle too much pressure.

Ortloff says this gets complicated when you realize the average pipe piece was about a foot long, and lines from a single spring (Ain Mousa) through the Siq could comprise nearly 42,000 connections. Plus, there were significant drops between the mountain springs and the city in the valley.

The Nabataeans used clever techniques to solve these problems.

First, many cisterns and water collection points were located around the city. This not only distributed water but also filtered out heavy particles in areas where water flow slowed. Each collection point also acted as a break in pressure on the pipeline, saving the weak joints.

Second, the Nabataeans used gradual angles to slow down water flow. Ideally, if the pipe wasn’t filled with water and there was an air barrier above, there was less pressure on the pipes. The Nabataeans turned this into an art form.

In an episode of NOVA, Ortloff studied the ideal angles to tilt a pipe to effectively move water under the least pressure. Slight changes made a big difference. A four-degree slant is perfect, whereas a six-degree angle could cause a catastrophe.

As Ortloff studied the terracotta pipe's remains in the Siq's walls, he noticed something startling. They were at exact four-degree angles.

While the obvious architecture and beauty of the stone structures of Petra captivate most, the hydraulic engineering the city rests on is the actual monument. But the two together in the same metropolis made me realize something.

Creating A Lasting Legacy Without Words

As I’ve read many reports of archeologists who’ve worked at or studied Petra and the Nabataeans, there was a continuous refrain. The researchers lamented that these ancient people didn’t leave many written records.

Not only this, but they didn’t leave much written on the stone they regularly carved. I think I know why. Muhammad Ali once addressed his nature of bragging by telling a reporter that it’s not bragging if you can back it up.

The Nabataeans didn’t have to write about their greatness. It was apparent by looking at their creations. Imagine stepping out of the desert, moving through the Siq, and being greeted by that stone mansion etched into a cliff. But this was just the beginning.

Where the land outside was dead and dry, within Petra, water flowed everywhere in such abundance that the Nabataeans flaunted it like gold chains. Not only was precious water present to drink, but it was also available for art and pleasure. It must have been like a miracle for a sun-beaten traveler.

Olympic-sized pools, gardens, pavilions on islands, mind-bending architecture, hydraulic engineering ahead of its time, and a trading empire existed in one of the harshest environments on Earth.

Why would you need to write about your greatness after you created a kingdom of water in the desert? Moreover, Dr. Bedal says only about three percent of Petra has been excavated.

So, there is no telling what other wonders are still hidden under the sand.

-Originally posted on Medium 7/5/24