Homer's Odyssey Shows A Better Way To Navigate Our Ever-Changing World

The ancient Greek idea of Métis and a harbor mind can help us deal with our unsettling times

Something has changed, and I’m sure you can feel it. The world isn’t the same. It’s hard to put this into one word or idea but it feels like we’re in the middle of a storm which might not end.

I believe Hudson Fellow and author Walter Russel Mead comes closest to identifying what’s going on. He sees another human epoch on the horizon like the Industrial and Neolithic revolutions. But this revolution will set off an “age of information,” which will be driven by ones and zeros.

Whereas the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions occurred over long periods, our age of information will be fast. I mean chaotically fast. In fact, for those living in our time, it’ll seem like one endless revolution that won’t stop.

You might compare it to being on a turbulent sea, where you can’t get your bearings. It’ll be terrifying and exciting simultaneously. The only constant will be an unsettled feeling of confusion because of the blinding changes.

So, how do our old, settled minds deal with this new age?

Well, the ancient Greek poet Homer left us an instruction manual thousands of years ago in his epic The Odyssey. Namely, their concept of Métis and a harbor mind should be our guide. But before we get here, we need to answer a question.

What would the ancient Greeks know about our chaotic times of endless change?

A Life Driven By The Sea And Harbor Minds

“We may want fixed answers…but we must know in the end to stay afloat, stay with the questions, and entertain doubt as the unlikely bedrock of understanding.”

— Adam Nicolson, How To Be: Life Lessons from the Early Greeks

In his book above, Adam Nicolson says after the Bronze Age collapse, a new world emerged. Ancient empires disappeared or withdrew. Suddenly smaller kingdoms and groups had room to expand on their regional stage.

He says this is where the ancient Greeks came into their own. They created a mesh of trade networks across the Aegean Sea around 800BC and built something new. Nicolson says they sought out a space between autocratic rule and anarchy. He calls it the “inventively civic.”

These Archaic Age Greeks weren’t the ones we’re familiar with that conquered the Persians. They were small harbor communities. Their life revolved around the sea, trade, and connections with other ports.

While the ocean was home, it was dangerous, and anything could and did happen. Force couldn’t help you here. For the ocean was force — a force so powerful it couldn’t be resisted. The writer of the Odyssey, Homer, came from Smyrna, one of these growing harbor communities.

Nicolson says 7th century BC Smyrna “was a society more about cleverness, then about heroism or dominance.” The sea required inventiveness, not brute force. The Greeks “lived in a fluid world and thought with a harbor mind.”

The unknown forced them to constantly ask questions, setting the bedrock for the future world of Greek thought we’re familiar with today. The ancient philosopher Heraclitus once quipped the only constant in life is change. Nicolson says this idea climbed out of the sea.

This harbor mindset also birthed the idea of Métis.

Creative Imagination Is Humanity’s Magic

“The Iliad and the Odyssey are a pair of true-crime classics; nothing gets done in either one until someone gets sneaky. And that someone is usually Odysseus, whose rogue’s eye made him the greatest of the Greek heroes.”

— Natural Born Heroes, Christopher McDougal

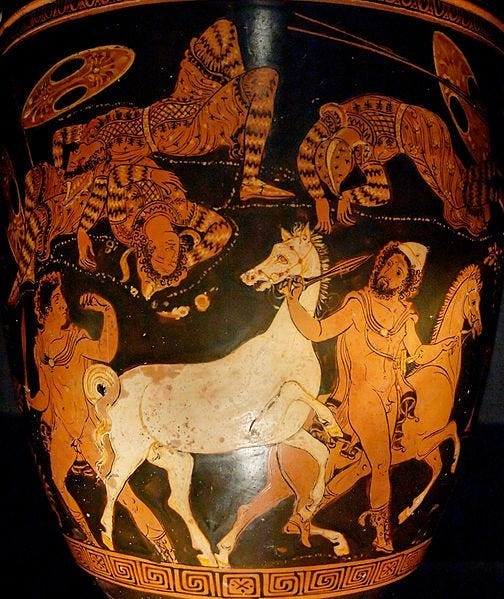

Odysseus was a thief, and the ancient Greeks loved him for it. Christopher McDougal in his book above points out the Greeks saw theft as cleverness. In fact, it was closer in their minds to a magic trick.

They even had a god devoted to stealing and lying: Hermes. Their mythology is full of wonderful ruses and thefts as well.

Jason stole the Golden Fleece.

Prometheus stole fire for the benefit of us measly humans.

For the Greeks, wealth was perishable, and anyone could take it from you (like a clever thief). So, you wouldn’t be remembered for your money. You’d be remembered for your Métis, or “creative imagination.”

But it wasn’t necessarily about theft, more ingenuity, and thinking through problems. That was the act of magic. Moreover, for sailors dependent on the unpredictable sea, navigating chaotic markets in other ports, and ever- changing alliances, Métis was a requirement.

The Greeks even changed the nature of their gods to reflect it. Before this time, Poseidon the powerful, unthinking, and violent god of the sea was a dominant deity. His son, the dull-witted cyclops reflected this too. But the Greeks changed their favor to the goddess of wisdom and war Athena.

According to Nicolson, Poseidon and the cyclops:

“Are the enemies of Odysseus, and the two of them stand on the other bank of the great divide, that separates the past from the future. Poseidon and the cyclops for large brutishness, and being no other than what they are. Athena and Odysseus for nimble light-footedness — the spirit of the thinking mind.”

Homer uses these characters of Odysseus and Athena to give a master class on being a creative thinker, while the later Greeks acted out this lesson in a time of need.

Athena, Odysseus And Shepherd-Thieves

During a point in the journey of Odysseus, he’s captured by the cyclops Polyphemus. The creature plans to eat the hero and his crew, and asks Odysseus his name, to which he replies, “Nobody.” He later tricks the cyclops three times.

Odysseus manages to get the creature drunk, then puts out its massive single eye while passed out. Polyphemus cries for help. But as a neighboring cyclops asks who’s hurting him, Polyphemus replies, “Nobody,” and his cries are ignored.

Afterwards, Odysseus disguises himself and crew in sheep skins to escape from the blind cyclops’ cave-prison. Athena displays similar acts of Métis.

While Odysseus is away at war, neighbors move in on his kingdom, trying to force his wife into marriage, while his young son Telemachus is unable to help. Nicolson says an older pirate lord suddenly appears, appropriately named “Mentor.”

But this older man is actually Athena in disguise. Mentor tells the young man “he must become a pirate captain trader too,” and teaches him “how to deal,” in a chaotic world where Métis is required.

According to Nicolson, the “goddess of cleverness” bends the boundaries of truth, or a single path, enabling the user to become many things: pirate, trader, captain, teller of tales, and liver of those same tales. Afterwards, Telemachus changes and becomes an aid to his mother, and stronger.

About 2500 years later as Nazi Germany invaded the Greek island of Crete, the locals showed the same Métis. In his book, McDougal says a group of Cretan shepherds caused so many problems for the invaders, the Germans needed to keep 30,000 troops to contain the island.

Despite the occupying presence, those same Cretan thieves managed to make a high-ranking general in the German army disappear. The rebels along with some British agents spirited General Heinrich Kreipe off the island right under 30,000 noses.

After the war, Hitler’s Chief of Staff, Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel gave the Greeks some credit for Germany losing the war due to delays starting the invasion of Russia. So, what do we learn from all of this?

We Need A Harbor Mind And Mêtis Right Now

While Walter Russel Mead points out the coming age of information will be chaotic and unsettling, the ancient Greeks dealt with the ultimate unsettling thing, the sea. But they didn’t let Poseidon overwhelm them. They developed a harbor mind and Métis, then conquered their world.

Being a small business owner, I’m well familiar with this chaos. During the ridiculous lockdowns, we were forced to develop new products, take advantage of shortages, and solve countless problems. We had to be our own Mentors, and teach ourselves how to deal.

As we’re hit with wave after wave of change, we’ll also be given countless opportunities to display a fluid harbor mind and take advantage of them. Athena and Odysseus may be characters, but their skills aren’t fiction.

We’re not called on to be thieves but are required to use creative imagination. It’s something we can even practice. Instead of complaining, we could be solving the many problems around us — especially the small ones. They’re our workouts to build a harbor mind and Métis.

So, how do our old, settled minds deal with this new age? We take a lesson from Homer and The Odyssey.

-Originally posted on Medium 2/5/24