Breaking Our Addiction to the Never-Ending Now

Escaping the mindless flashflood of data with help from the past

Data was once something precious.

Before the written language, important things were handed down by oral tradition for thousands of years. For instance, it’s believed one tale told by an Aboriginal group in Australia about a volcano has been handed down for over 7,000 years.

But only so many stories could be spread this way.

As humanity perfected writing, the stories increased and got more complicated. For instance, about 4,000 years ago, the first listicle was created. A government official named Ptahhotep jotted down a numbered list of forty-three wise ideas for his son to think about as the boy replaced his father in service to the pharaoh.

Only so many were literate, though. Over countless years, these few literate scribes in Egypt used Ptahhotep’s wisdom as an instructional tool to learn writing — copying the wise ideas over and over on papyrus. It’s why we still have the Maxims of Ptahhotep today.

Presently, things are very different. Data is cheap, literacy has increased dramatically, and video has enabled the oral word to spread quicker than a volcano blasting out magma over an ancient landscape.

For instance, the Guardian reported that the equivalent of ninety percent of the data generated in the history of the world was created in the years 2012 and 2013. By 2024, we’ve hit twenty times this already staggering amount. Consider it a digital tsunami of new information.

I find myself surfing this massive wave of information daily, getting pushed wherever the swell feels like dropping me, often losing thirty to forty minutes at a time. Many others tell me the same thing. But blogger and podcaster David Perell noticed something many of us miss.

Perell found most of the information he and his friends consumed was created within the past twenty-four hours. He calls this funnel of information the “never-ending now,” and sees it as an endless consumption of the recent present.

Former Google engineer Joran Tigani agrees, explaining most data that gets processed is less than twenty-four hours old. Also, by the time it ages a week, it’s twenty times less likely to be queried. What’s more, we’re not just drawn to this never-ending now, the social media we spend so much time on addicts us to it.

Social media companies are so aware of this that they’ve even calculated how long it takes to hook us on their product.

In a recent lawsuit by fourteen state attorney generals against TikTok, it’s been revealed company management formulated a user needed to watch 360 videos before they became addicted. Since many of these videos are short, it translates to only thirty-five minutes of viewing before we’re hooked.

So, those thirty-to-forty-minute trips on that data tsunami aren’t just time wasters, they’re our gateway drug to addiction into the never-ending now. But there is a simple therapy to help us.

Exposure Therapy To The Past

Ultimately, the greatest defense against a flood of cheap data that gets consumed and forgotten about like fast food is higher-end data—in other words, digesting classics. By classics, I mean information and ideas that have been around for not just a day or even a year but decades.

In our age, where most data is very short-term, things that can last way beyond this horizon have done so for a good reason. They contain something timeless, something that breaks down that twenty-four-hour façade that encases so much we consume.

Rightly, some might wonder: isn’t living in the present moment a good thing? Well, yes. If you look up “living in the present moment” on Google, you’ll find endless explanations of how it can help you avoid ruminating on the past and worrying about the future.

But being stuck in the never-ending now has its own problems.

It causes us to lack perspective, catastrophizing events of the present way out of proportion compared to historical examples (i.e.- things have never been worse than today.)

It makes us unable to step out of the chaotic now and detach our emotions from the moment.

It distracts us from timeless golden ideas by flooding us with cheap data designed to be consumed and forgotten, followed by equally forgettable replacements after that.

It causes us to ignore opportunities those timeless ideas can provide.

This last bullet point gives us a quick starting point for treating our addiction. Consider it an exposure therapy, slowly giving us basic reasons why classic information is so valuable, and the benefits of timelessness.

See, classics aren’t just books; they can be products and ideas, too.

Profiting From Timeless Ideas

“Our emblem is inspired by a bas relief found at the old Royal Wax Manufacture which used to belong to the Trudon family…Our motto, ‘Deo Regique Laborant’, which you can read on our emblem means: the bees work for God and the King.” — Cire Trudon Website

In a famous interview Jeff Bezos once explained the success of his company Amazon isn’t based on technology. It comes from focusing on things that don’t change. Bezos said whether today, or ten years from now, people would desire fast delivery and lower prices. That wouldn’t change.

Likewise, author Ryan Holiday says other companies have adopted a similar strategy and have thrived for hundreds of years. In his book Perennial Seller: The Art of Making and Marketing Work that Lasts, he says French firm Cire Trudon has been selling scented candles since 1643.

These candles have been used in the court of Louis XIV and Napoleon. Moreover, they’re still thriving, opening a location in NYC in 2015. While electricity and LEDs should have put them out of business long ago, there’s something timeless about the scent, bee’s wax, and flame.

Holiday says it’s the same for Zildjian. This company, based in Constantinople, has been making symbols used for drums since 1623. Moreover, Fiskars, a scissor manufacturer, has been around since 1649. Synthesizers and electric clippers couldn’t kill them.

But Ben Dooley and Hisako Ueno, in their article in the New York Times, say this is child’s play. A small shop in Kyoto called Ichiwa has been in business since the year 1000. What do they sell? Rice flower cakes and tea, nothing else.

Dooley and Ueno say this is one of nineteen companies in Japan that are this old. In addition, over a hundred are at least five hundred years old, and over three thousand are at least two centuries old.

While many firms seek to maximize profits and grow, many of these old “shinise” businesses are family-owned and focus on family precepts called “kakun.” They often deal in traditional goods and services, expand slowly, if at all, and aim for survival so they can continue to the next generation.

Risk isn’t part of their vocabulary, and their traditional goods and services buck trends and fads. So, they quietly scream “timeless” over multiple generations. As the owner of a second-generation family business that focuses on a niche area, I can understand.

But there’s a more traditional form of classics that can insulate us from the never-ending now in a different way.

Growing From Timeless Wisdom

While data has lost its luster and staying power, there are still timeless gems that shine throughout the ages and defy the TikTok addiction trends of the minute.

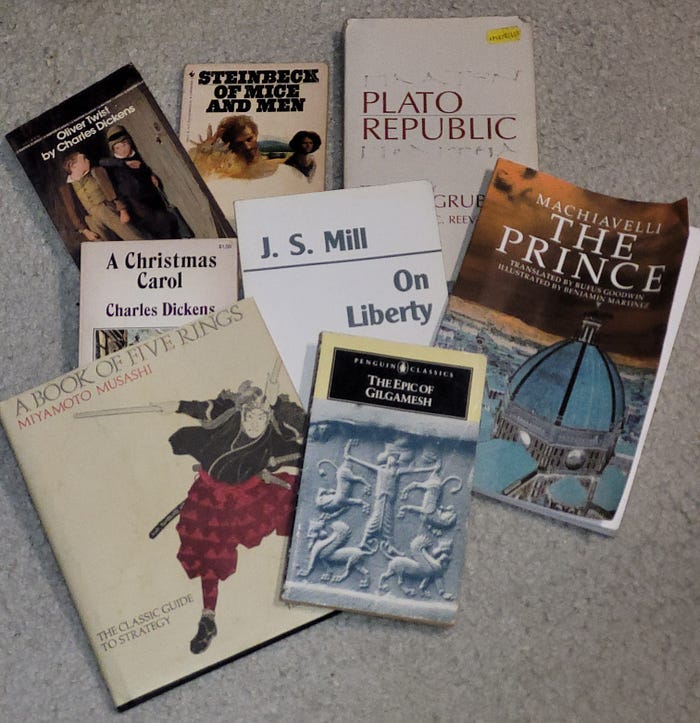

The Epic of Gilgamesh was originally found on clay tablets in Mesopotamia, dating back to about 2100 BC.

Plato’s Republic was written about 375 BC.

Machiavelli’s The Prince was published in 1532

Musashi’s A Book of Five Rings was written in 1645.

Out of the others, the latest written (Of Mice and Men) is about seventy years old.

Despite its age, Gilgamesh deals with humanity’s fear of mortality and the impossibility of living forever. Plato’s Republic is a timely discussion about justice (for the individual and state), while Machiavelli and Musashi delve into timeless psychological lessons ideal for our age.

In The Prince, the pragmatic Machiavelli points out perception is reality, saying:

“Men judge more by appearances than by deeds. Everyone can see, few people can actually perceive and judge. Everybody can see what you seem to be; few can judge what you actually are.”

While the samurai and philosopher Musashi explains in A Book of Five Rings, the fortitude you gain by doing difficult things is a transferrable skill that makes other difficult things easier. He says, “If you know the way broadly, you will see it in everything.”

But the greatest thing is we’re not just limited to the physical books above. We can even have the classics read to us on our phones. Last week I conveniently listened to Man’s Search For Meaning, while sitting in traffic.

Its author and holocaust survivor Dr. Viktor Frankl pointed out that no matter how terrible our lives are, we can find meaning in them. He eloquently states:

“It is possible to practice the art of living even in a concentration camp, although suffering is omnipresent.”

As you can see, there’s a reason why such classics resist the ravages of time. Moreover, the same digital world that floods us with nutritionless mind candy can also give us easier access to quality timeless information.

And this is the secret for dealing with the never-ending now.

Our Classic Defense

While the dealers of addictive instant content attempt to hook us, we’re not destined to become addicts. Classics can vaccinate us against the TikToks of the world. Moreover, these timeless ideas are now as easy to access as a YouTube video.

So, whether it be the words of Ptahhotep, the smell and light of a Cire Trudon candle, or a lesson on meaning from Frankl, these classic ideas can form a strong anchor to protect us from the storm of the chaotic present.

Data may no longer be precious, but classics by their own nature are timeless and immortal. I know, at least in my own life, this anchor will be critical in the future as the world speeds up and the never-ending now tosses me around like a rogue wave.

Hopefully, you have a favorite classic to hold you down as well.

-Originally posted on Medium 11/3/24