As a Kid Doctors Gave Me a List of Things I’d Never Be Able to Do

It was the greatest gift anyone has ever given me

Humanity has an innate fairness problem. It becomes apparent with two of the greatest questions we all ask at one point or another.

Why do bad things happen to good people?

Why me?

We scream these questions to no one in particular, out loud, or within our own minds. They rarely receive a good answer. Even our primate ancestors understand fairness, so I think it naturally irks us when the world is unfair because it’s built into us to notice.

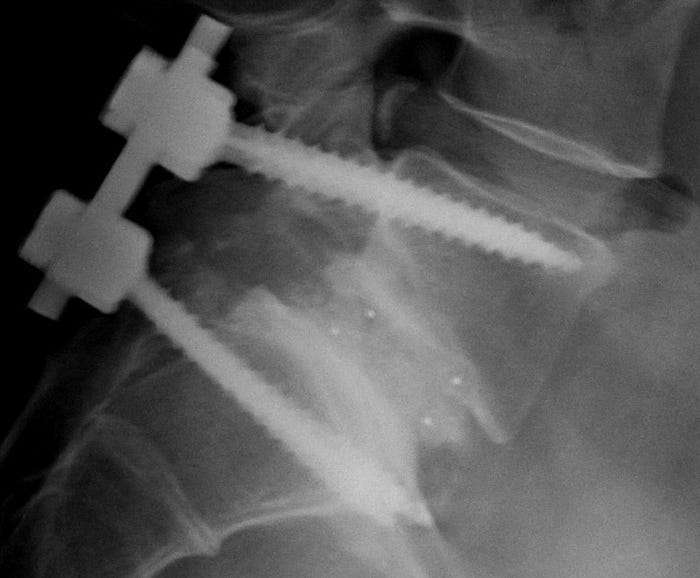

One of my first major “why me / unfair” moments happened as an early teen. After consulting with some doctors, they told me I needed a spinal fusion immediately. Sometime before the surgery, they handed me a paper unexpectedly with activities I’d never be able to do for the rest of my life.

But this wasn’t their only gift.

I missed half my freshman year in high school and had to go to a summer school with juvenile delinquents while stitches held my back together.

Sports I wanted to play were out of the question.

The surgery resulted in back pain and stiffness I’d have to deal with the rest of my life.

I didn’t handle this well. For a few years, I was a miserable bastard because life wasn’t fair. Later I learned the two questions I kept repeating: “why me,” and “why do bad things happen to good people” were the wrong ones to ask.

A philosopher long ago had found a much better question. Now, I understand that surgery and paper were a gift. But it makes more sense when you realize nothing comes for free.

Choice And Paying The Price For What It’s Worth

Long ago a man name Epictetus spent his early life as a slave in the Roman Empire. Eventually he won his freedom. He devoted his life to philosophy, becoming one of the greatest teachers in the empire. Even emperors were rumored to have attended his lectures.

Not only did he share his philosophy of Stoicism but he spoke with the authority of a person who’d been through hell and back.

In How to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic Life, Anthony Long translates recorded lectures from Epictetus. Many involve two views on fairness. The philosopher doesn’t sugar coat anything stating:

“Keep in mind that you cannot expect to get an equal share of the things that are not up to us, without doing the same things others have done.”

His first view on fairness involves those who have it “better” than you.

Epictetus says everyone pays for what they have in some way. You just don’t see the cost. It may have come at brown nosing, sweat, pain, endless hours with no peace, and maybe even a part of their soul. Nothing comes for free.

Epictetus often talks about the obsession of Olympic athletes.

This is something Will Ahmed, the CEO of the fitness tracking company WHOOP, knows well after working with countless professional athletes. In a recent interview, he says great athletes “have a drive that they’re tormented by,” and are “willing to sacrifice everything else for it.”

So it doesn’t pay for us to envy others and say, “why me.” But there’s also the second issue with fairness, or the pain caused by bad things that happen for no reason. Epictetus’s answer for this is choice.

In a lesson gained from his time in servitude, he explains that even if your body is chained, your mind isn’t. There’s always a choice in how you think about events. In other words, change the question you ask yourself.

Instead of the unanswerable “why me,” or “why do bad things happen to good people,” change the question to “what can I do with this?” This question always has an answer, although it may take some time to figure it out. There are endless examples of this.

Choosing What To Do With The Cards We’re Dealt

Sometime around 1886, a boy named Wilbur was playing hockey with other kids. He was athletic, outgoing, and planned to go to Yale after graduating high school. During the game, another boy, who eventually became a serial killer, attacked Wilbur with a hockey stick. The event changed his life.

Wilbur lost most of his teeth, became withdrawn, never finished high school, and spent most of his time at home reading and paling around with his little brother Orville. The two often spent time tinkering with machines. About seventeen years later, the Wright Brothers figured out flight.

Amanda Knox had her own strange path as well. In 2007, she became infamous through none of her own doing, after her roommate was murdered in Italy. Amanda was unfairly sentenced to over twenty years in prison for the crime she didn’t commit.

She was acquitted after nearly four years in prison. In an interview with NPR she notes:

“I felt so alone and so ostracized for so long, and not just when I was in a prison cell…I felt very alone when I came home until I realized that we all, at some point in our lives, have external things happening to us that we can’t control that make us feel like we’re trapped in our own life and that we are not the protagonists of our own life.”

She later reached out to the prosecutor who unfairly tried her. They began a correspondence. Strangely, the relationship gave her a sense of power back, and the prosecutor admitted if he had known the real Amanda, he would never have tried to sentence her.

Amanda now works helping those wrongfully accused and is trying to become a link between victims of crimes and those illegitimately prosecuted. Teddy Atlas likewise had his own encounter with prison, but it was deserved.

Atlas’s father was a famous doctor who helped the poor throughout New York, but he ignored Teddy. So, the son came up with a plan. He’d completely break himself, that way his father would notice him.

Teddy began getting into fights, robbing people, and spent some time at Rikers Island prison. It all came to a head when Teddy got slashed with a knife that missed his jugular by a centimeter and cut all the way up to his skull.

It required four hundred stitches to fix (two hundred inside, two hundred out.) To stay out of trouble, Teddy got into boxing and met a famous trainer named Cus D’Amato who saved him. Cus talked the young protégé into becoming his assistant, which eventually involved training a teenage Mike Tyson.

Cus later kicked Teddy out of the boxing camp after a disagreement over Tyson’s behavior. In a discussion with Lex Fridman, Teddy calmly addresses his firing and loss of a mentor stating:

“I got the benefit of a career. I got the benefit of knowledge. I got the benefit of a life. I got the benefit of learning and hopefully becoming a better person, and I got the benefit of being betrayed.”

Atlas thoughtfully mentions terrible things can give us opportunities. He says, “Fear causes…a lot of problems, and it also solves a lot of problems. Without it, we could never be great.” And most people avoid facing fear, resulting in regret, and “regret is the worst thing in the world, because it’s a solitary sentence.” Dr. Edith Eva Eger’s lessons came at a higher price.

A contemporary of Viktor Frankl, Eger also spent time in concentration camps in her later teenage years, losing her mother and father. In her book, The Choice, the former ballerina tells her story of abuse, near starvation, and being forced to dance for Dr. Josef Mengele.

Towards the end of the war, American soldiers found her boney body in a pile of corpses and helped nurse her back to life. Later Eger became a clinical psychologist in the United States, focusing on those suffering through trauma. Her time was often invested in helping soldiers.

She traveled to many U.S. military bases, helping those with PTSD, depression, and giving talks. But one visit left her speechless. Upon facing a group of soldiers, she became overwhelmed and kept noticing an image she recognized. It was the symbol of the 71st Infantry Division. Those were the soldiers who liberated her.

After so many years, she was facing that symbol again, and this time she was trying to save her liberators. Eger calls her book The Choice, because she believes we all have a choice on what to do with things life throws at us. It’s that better question of “what can I do with this.”

On a lesser note, it also brings me back to that list I was handed as a kid.

Why Heroes In Stories Must Suffer

“I know things about Teddy Atlas this court doesn’t know. Things you won’t find on his arrest record. This boy has character. He has loyalty. He’ll hurt himself before he’ll let down a friend. These qualities are rare, and they shouldn’t be lost…If we lose him, we’ll be losing someone who could help a lot of people. Please don’t take this young boy’s future away. He could be someone special.”

— Transcript of Cus D’Amato testifying on behalf of Teddy Atlas, The Lex Fridman Podcast

Steven Pressfield is one of my favorite authors. His books include classics like The Legend of Bagger Vance, Gates of Fire (which is taught at the US Military Academy), and The War of Art. He can also give some major lessons about fairness and dealing with bad breaks.

During a recent interview, he reveals it took thirty-five years of trying before he ever penned a successful novel. So, he spent years penniless banging away at a typewriter. Pressfield notes all good heroes in books need to suffer because it makes a good story.

The story is so appealing to us…because we all suffer, usually unfairly. And we like to see how heroic characters deal with it, or make something out of the pain.

I did this poorly at first. That paper the doctors handed over crushed me, and I didn’t know how to react to the events after my surgery. Years later, I see differently.

Without the surgery, I would never have found innovative ways to exercise, which keep me fit to this day. I also would never have gotten into martial arts. Finally, the strange ways life pushed me also got me to write and study philosophy. I wouldn’t have met many of the people I know now without the surgery either.

Everything has a price, but often you must pay it upfront without knowing what you’ll get in return. I spent way too much time asking, “why me,” and “why do bad things happen to good people.” But once I started asking “what can I do with this,” many things changed for the better.

As a kid doctors gave me a list of things I’d never be able to do. It was the greatest gift anyone has ever given me.

A wonderful, and quite personal, read. Thank you!