A Christmas Carol’s Message About Ending Our Self-Hatred Of Humanity

Ebenezer Scrooge has words of hope we all need this season

I’m a natural pessimist. Even worse, a wiseass lurks deep within me, always waiting for the appropriate moment to spike a comment through something or person. This keeps an innate radar up within me, looking for opportunities.

But this radar has noticed an almost unnatural cynicism from every angle over the past few years. I’d say it nears hatred. And the weirdest part is the target of the loathing: humanity.

As a species, we oddly dislike ourselves. I’ve even seen many refer to humanity as a virus or a parasite. Moreover, in Better To Have Never Been, Dr. David Benatar even argues things would be much better if we never existed. Although compared to others, he’s kind.

Entomologist Paul Ehrlich, in his well-received book The Population Bomb, saw us no different than the insects he regularly studied. Like bugs, he believed we’d breed until we outstripped the resources around us and starved. Hence, our population must be managed like a herd of deer.

I even found interviews with the affable William Shatner echoing Ehrlich. Yup, Captain Kirk too! Even for a smartass-pessimist like me, it’s too much.

Diminishing the value of humanity never leads anywhere positive. While it’s given some in the recent past genocidal license to act, our self-loathing isn’t a new phenomenon. Charles Dickens addressed it as well in the 1840s within his classic A Christmas Carol.

Early Ebenezer Scrooge Uses The Logic Of Malthus

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

— Ebenezer Scrooge, A Christmas Carol By Charles Dickens

The comment above might be the most chilling spoken by Ebenezer Scrooge throughout the story. He says these words as he denies requests by charity workers. He’s coldly implying if the poor just died, we’d have more resources. Or you may say it would be better if they’d never been.

It’s a literary device to show the coldness of the fictional character. But this wasn’t fiction. Starving the poor to decrease the surplus population was government policy in England of Dickens’ day.

In an article in Scientific American, science journalist and author Matt Ridley says England passed the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which cut food aid to the poor. Oddly, they did it out of mercy. Because if you feed the poor, they’ll breed more, creating a surplus population.

The idea came from Thomas Malthus’ Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. In it, he predicted humanity would breed itself into starvation, like any other animal, although that didn’t happen.

Malthus came to this conclusion by looking at the bloated population of London, which he attributed to breeding. But it was due to migration. Chelsea Follett points out at Human Progress.org that people relocated from the countryside to the city for jobs. Plus, more survived illness. The increased population led to innovation, which created more food.

But Malthus never went away. He resurfaced again in Paul Ehrlich's words, and people acted out of mercy.

An Old Ghost’s Warning Fit For Our Age

My favorite formulation of Dickens’ story is the 1984 version of A Christmas Carol. During a gut-wrenching scene, Scrooge asks about the future of the sick child “Tiny Tim,” and The Ghost of Christmas Present brings up the earlier “surplus population” comment. The Ghost says:

“Perhaps in the future you will hold your tongue, until you have discovered what the surplus population is, and where it is. It may well be in the sight of heaven you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child.”

Scrooge instantly realizes it’s hard for a population to be “surplus” when a familiar child’s face is attached. A parasite becomes harder to wipe away when it has a name. Now, if only this Ghost visited Malthus or Ehrlich.

The latter’s book convinced the World Bank and United Nations to act. They’d start in India. The groups worked with Indira Gandhi to begin mass sterilizations. But author Vinod Mehta explains no one volunteered for the programs, even for money.

So, Gandhi’s son began rounding up the poor and sterilizing them against their will. He killed those who resisted. Soutik Biswas, in his article for the BBC, notes India sterilized over six million men within a year in 1975, which was fifteen times more than the Nazis performed.

Ehrlich’s overpopulation ideas also encouraged China’s One Child Policy, which resulted in forcing possibly a hundred million abortions and sterilizing millions. Other sterilization programs were enforced in Mexico, Bangladesh, Peru, Indonesia, and Bolivia too.

Obviously, this is dark, but it only gets worse when you truly view humans as nothing more than a parasite or virus.

Exterminating Useless Insects

When you equate a population’s worth to the value of parasites or insects, extermination is a possible solution for the problem. You find many examples of this in history. Hitler referred to an entire population as parasites, and even used a tool one might for insects.

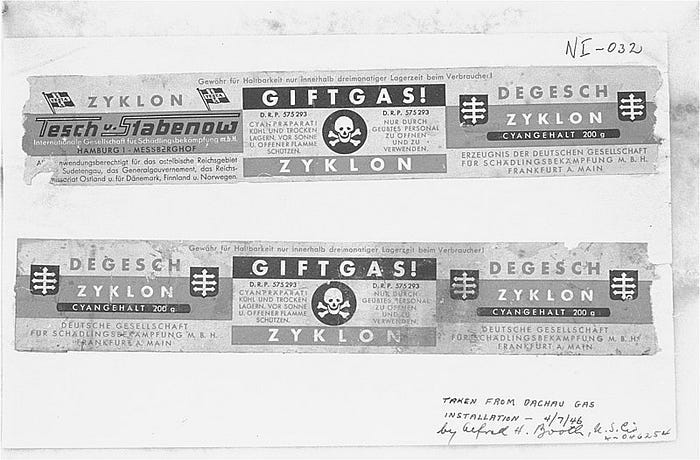

Zyklon B gas was originally used as an insecticide to delouse clothing before it was repurposed for gas chambers. But this wasn’t the only incarnation.

This type of thought became logical when dealing with parasites and worked its way into an office meeting of German staff on May 2, 1941, during the planned invasion of Russia.

A group of Nazi ministers devised a plan to starve twenty million Russians. This served a dual purpose. It got rid of parasites and procured more food for the German empire.

The Soviets also saw Ukrainians as parasites too and starved them in countless numbers during the Holodomor. Then, there was the Khmer Rouge. They took pictures of their victims in Tuol Sleng prison before they bashed their heads in with clubs, keeping the photos like those of a scientific specimen. Only a dozen or so survived, out of fourteen thousand.

But this idea of seeing humanity as a parasite or virus demeans others and ourselves. Thankfully, Dickens shows us a path to salvation.

Learning Forgiveness For Ourselves And Our Kind

Despite Scrooge's self-absorption and coldness, he finds forgiveness in the end and learns to love humanity. But forgiveness is an odd creature. We usually think of it in terms of one forgiving another; however, one must also learn to forgive themselves. Without it, self-torture is the result.

I work near one of the largest open-air illegal drug markets in the United States. Addiction is a monster. I see many living on the streets, abandoning their families and hope, often powered by shame.

I didn’t understand this for the longest time until I researched a local woman living on the streets that got set on fire. She was interviewed beforehand and said she’d avoid her family if they looked for her; she didn’t want to be found.

This woman and others there see themselves as parasites or “surplus population” — only hurting the ones they love.

Self-hatred can manifest itself in the strangest of ways. One can only imagine what it does to our kind when we’re continually assaulted with the notion we’re a virus.

It’s time we end the hatred of humanity and forgive ourselves. I’m not a parasite, neither are you, nor the decedents we leave behind. Moreover, Dickens’ message is just as relevant and needed as it was in his day.

Scrooge’s Message Of Hope For Our Time

The self-hatred we express today also existed in 1840s London. The language has changed, though. Their “surplus population” turned into our parasite or virus, although both sets of terms are equally acidic. First, they make us forget the more honorable accomplishments of humanity.

Professor and scientist Vaclav Smil points out that one of the wonders of the twentieth century is synthetic ammonia. It’s created by pulling nitrogen out of the very air, which can be used as fertilizer. Smil says this feeds at least forty percent of the world’s population, avoiding mass starvations predicted by certain entomologists.

According to Our World In Data, global childhood mortality reached forty-three percent in 1800, but by 2015, it had dropped to four percent. Imagine living in a world where four of every ten kids you knew died.

Historian Will Durant reminds us flight isn’t a recent interest. Humanity has been focused on leaving the ground for three thousand years. It began with the stories of Icarus, continued with Da Vinci creating flying machines, and built to a crescendo with the Wright brothers. Humanity landed on the moon within only sixty years of their first flight.

Second, the self-hatred of the parasite/virus trope has also kindled Holocausts, enacted forced sterilization campaigns, and driven addicts to isolation on the streets.

A certain Ghost of Christmas Past might urge us to “hold our tongues” when we damn our own kind as a virus. After all, this “virus” has a name, face, and soul. It’s time we forgive ourselves.

Hopefully, Dickens’ message haunts us pleasantly every December. We need the yearly therapy in Scrooge’s story of forgiveness and love of humanity to overwhelm the self-hatred we’re so fond of.

-Originally posted on Medium 12/2/23