A Better Way To Navigate The Overwhelming Flood Of Data In Our Lives

Epicurus, a mythical library, and finding alternatives to gamification metrics

Writing is a special kind of heaven and hell. The heaven part happens after I’m done, and pieces magically come together into a functional whole, which I couldn’t entirely see previously. The hell is more generic.

For me, it involves mining ideas from a flood of data that often proves to be useless. I tend to flail in this river. My mind is pushed around from current to current, looking for a firm branch of thought to brace myself with.

Although you don’t have to be a writer to be caught in this data flood; nowadays, we can all become victims to its torrents.

Statista estimates by 2025, the world will generate 181 zettabytes of data. If you’re not familiar, a zettabyte is a trillion gigabytes. For reference, the average smart phone can store about 100 gigs of data.

So by 2025, we’ll be generating almost two billion smart phones’ worth of data.

That’s a flow of information too powerful to sip from, and destabilizing in many ways. Add AI to this, our increased time in a virtual world, social media, and machines replacing us in everything imaginable, and this gives you a technological existential crisis.

But it’s not entirely unforeseen. An odd cast of characters has weighed in on certain areas of the dilemma, and between the group, they can give us a better idea on managing the data deluge.

Our first stop is an infinite library in a work of fiction, which sounds a bit familiar to our tech world today.

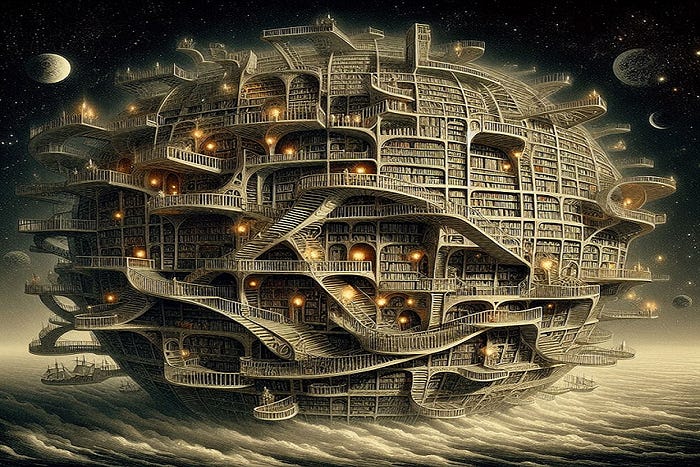

The Library Of Endless Wisdom And Nonsense

In 1941, Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges penned a short story called The Library of Babel.

A librarian, acting as narrator, explains no one knows when the mysterious structure was created, how large it truly is, or its purpose. However, it appears truly massive — in fact — infinite and otherworldly.

Sometimes the narrator even uses the term “library,” and “universe” interchangeably, and says:

“Man, the imperfect librarian, may be the work of chance or of malevolent demiurges; the universe, with its elegant appointments — its bookshelves, its enigmatic books, its indefatigable staircases for the traveler, and its water closets for the seated librarian-can only be the handiwork of a god.”

The library itself is made of hexagon-shaped rooms, each with five book shelves, holding thirty-two books. All books have four hundred ten pages, each page the same amount of lines, and every line about the same number of text characters.

But that’s where the well-crafted design of a creator ends. The librarian says, “For every rational line or forthright statement there are leagues of senseless cacophony, verbal nonsense, and incoherency.” The only consistency is the use of twenty-two alphabetic letters and three symbols. Most books contain gibberish.

Due to the mysteriousness and grandeur of the structure, the librarian residents believe it contains all the books and knowledge ever created. Joyfully they scour the library searching for the treasure of wisdom. A lack of discovery is only due to the size of the structure.

But the long searches become fruitless, and depression sets in. It’s imagined one book could break the code to all others, but this text happens to always be just out of reach.

Elation switches to chaos, with librarians attacking each other, destroying books to limit the nonsense, and attaching themselves to any strange belief to fill the void their unsuccessful searches leave open.

While many see Borges’ story as an allegory of our mysterious universe, others presently attach it to our flood of data which promises ultimate kernels of wisdom but these are often polluted with junk.

Like the librarians, we seek something to soothe our frustrations. A clever blogger thinks it’s being done with games.

Pigeons And Gamification

“There is, after all, a vacancy in heaven. When God is dead, and nations are atomized, and family seems burdensome, and machines can beat us at our jobs and even at art, and trust and truth are lost in a roiling sea of AI-generated clickbait — what is left but games?”

— Why Everything Is Becoming A Game, Gurwinder Bhogal

In his blog post above, Gurwinder Bhogal says the brightest minds in our world have been turning our lives “into a series of games.” This isn’t for our amusement, though. In fact, it’s the easiest way to control someone.

He points out that B.F. Skinner believed the environment could control behavior and sought to prove this through experiments with pigeons. The birds were awarded food each time they pecked a button. However, these pigeons continued pecking the buttons, even after they were full.

The birds became conditioned to hear the clicking of the food dispenser as a reward, whether it was spitting out treats or not. Skinner learned a lot from the experiment. First, there are two types of reward systems:

Primary reinforcers are things we’re born to desire: food, water, and warmth.

Conditioned reinforcers are things we’re trained to desire. They’re usually linked to primary reinforces, but are better for controlling behavior. For instance, even after the pigeons weren’t hungry, they kept pecking the buttons, because they were conditioned to value the sound.

Skinner also found out that immediate and unpredictable rewards were better than delayed and consistent ones. Consequently, the pigeons were more interested when a dispenser randomly spit out food (like a slot machine occasionally paying off.)

A corporate consultant in the 1970s took it a step further. Charles Coonradt noticed people put more effort in games they invest money in, than work they’re paid to do. So, he tried to make work like a game, shortening rewards in the feedback loop to “daily targets, points systems, and leaderboards.” According to Bhogal:

“These conditioned reinforcers would transform work from a series of monthly slogs into daily status games, in which employees competed to fulfil the company’s goals.”

By 2008, a new word appeared, “gamification.” Many organizations figured out ways to increase giving to charities, get people to exercise more, and discover answers to questions with associated games. But what else could it do? Bhogal says:

“We humans are harder to manipulate than pigeons, but we can be manipulated in many more ways, because we have a wider spectrum of needs. Pigeons don’t care much about respect, but for us it’s a primary reinforcer, to such an extent that we can be made to desire arbitrary sounds that become associated with it, like praise and applause.”

By 2009, Facebook had developed the “like” button. This became a way we could all garner status, so posting became an addictive enterprise with random rewards. Other apps followed suit. Bhogal says this turned social media “into the world’s most addictive status game,” and us into pecking pigeons.

The blogger says corporations and nations have adopted the strategy. The Chinese government developed a social credit system, which punishes those who don’t tow the line, displaying a score with leaderboards. Disney and Amazon do the same, showing workers’ statistics publicly.

It’s also caused a change in us. Where people once shaped society, now society shapes people into chasing artificial goals, such as likes. According to Bhogal:

“Today the evidence is everywhere: religion is dying out, Western nations are culturally confused, people are getting married less and having fewer children, and many are losing their jobs to automation, so the traditional pillars of life — God, nation, family, and work — are crumbling, and people are losing their value systems.”

It only makes us latch on to games more tightly, which give us order and fills the missing gap in our present society. Although games are a shallow substitute. Bhogal has some ideas to fix this, and they mirror an ancient Greek philosopher.

Epicurus: Unnecessary Desires And Uncaged Pigeons

Sometime around 300BC, Epicurus taught the default state of humanity was happiness and we diminish it with our unnecessary desires.

Ultimately, he believed we are all made up of atoms whose course was unpredictable and not controlled by fate. This lack of control gave us the free will to choose. Our happiness, therefore, depended on our choices in pursuit of two different types of desires: necessary and unnecessary.

A necessary desire is thirst or hunger. Without water or food you’ll die; however, if your desire for a vintage bottle of wine is denied, it only results in wounded pride. So that’s an unnecessary desire.

Consequently, taking pleasure in the necessary and simple, results in that innate state of happiness all humans are structured with. Chasing the unnecessary results in insatiable desires; therefore he’s putting limits on the unlimited world to stave off unhappiness.

So, that chaotic pursuit of the eternal in our Library of Babel only results in frustration. It’s better to restrict the firehose of data to the necessary trickle we need. It’s a similar story for gamification. Bhogal says it’s not bad in itself, and we don’t have to stop playing, just modify the game.

Pick long-term over short-term goals, these are less likely to lead to addiction. Also, imagine if your ninety-year-old self would be proud to have played the game you’re playing now.

Difficult games are better than easy ones. It’ll make you appreciate the reward even more, and build a better you on the way.

Play games where everyone benefits: education, wealth creation, and charity. Status games require one to lose for another to gain.

Choose games you enjoy over those you play for rewards. Statistics tend to turn games into work.

Rewards that can’t be measured are far more valuable than ones that can be quantified (i.e.- happiness, love, fulfillment.) Seek those.

Finally, when you step back and notice it all — the data library of Babel, the controlling games, addiction to meaningless short-term stats, and unnecessary desires — it gives you the power to play your own game.

As Bhogal notes, Skinner’s pigeons couldn’t leave their cages and fly away, while we can.

- Originally posted on Medium 4/21/24