1800 Years Before Pompeii, Mount Vesuvius Devastated Another Civilization

The other volcanic apocalypse in ancient Italy

We often associate history with people, and it’s hard not to. The root of the word history itself means investigation in Greek. That’s what the first historian Herodotus did; he traveled throughout the known world of his day talking to people as he went.

But history often has another powerful actor that shapes the story of people in ways beyond comprehension: the earth.

For instance, every 26,000 years or so, the earth’s northern pole completes a circle called the “precession of the equinoxes.” During this period, our North Star changes multiple times. In other words, the ancient Egyptians building the Great Pyramid of Giza had a different North Star than we do.

Sections of the Middle East we now associate with desert were once lush green areas where hunters chased massive herds of wild game. Moreover, the Mediterranean Sea, which carried Herodotus on his journey once dried up about six million years ago, and refilled in what some think was a cataclysmic flood worthy of a block-buster disaster movie.

But the disaster movie of humanity couldn’t be complete without volcanos.

In more recent history, we have Pompeii. It’s a time capsule covered in ash. Two thousand years ago, this Roman city stopped dead in its tracks and was buried by an eruption of nearby Mount Vesuvius.

It’s debatably the most infamous eruption of all time. However, Vesuvius has a long history before this, and it’s not the first time the fiery mountain devastated a human population.

There was also a Bronze Age eruption in about 1780 BC. Or as Prof. Claude Albore Livadie refers to it “the prehistoric Pompeii” in the documentary Vesuvius and the First Pompeii.

A Grim Time Capsule Of Prehistory

“A volcanic catastrophe even more devastating than the famous…Pompeii eruption occurred during the Old Bronze Age at Vesuvius. The 3780-yr-B.P. Avellino plinian eruption produced an early violent pumice fallout and a late pyroclastic surge sequence that covered the volcano surroundings as far as 25 km away, burying land and villages.”

— Mastrolorenzo G, Petrone P, Pappalardo L, Sheridan MF. The Avellino 3780-yr-B.P. catastrophe as a worst-case scenario for a future eruption at Vesuvius. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Mar 21;103(12):4366–70.

According to the documentary, in 1995 during a random excavation in Italy, two skeletons were found buried in pumice. It looked like the two suffered a terrible fate. The bodies were lying on their sides with their hands up towards their heads, trying to protect their faces.

Their position closely mimicked those found in the rubble of Pompeii. But the town where the bodies were found, San Paolo Belsito, is far to the northeast of that site. So, it was unlikely they were victims of the same eruption.

Volcanologist Dr. Guiseppe Mastrolorenzo explains by studying the sediment and pumice, the debris was identified as coming from the Avellino eruption, about eighteen hundred years before Pompeii.

This older eruption is named after the town of Avellino, which is about fifty kilometers away from Vesuvius, because the fallout from this explosion drifted northeast.

The two bodies were soon linked to pottery found buried in an ash mound in that area decades before. Eventually, an amazing discovery was made in 2001 in the town of Nola, close to Avellino, as the ground was surveyed for a future supermarket.

An entire Bronze Age village smothered in ash was left — Pompeii style. It looked like the inhabitants left in a hurry. Everything was in near pristine shape, giving a stunning view into Bronze Age life within Italy.

Life Frozen In Time

In the documentary, Prof. Claude Albore Livadie says no one expected either the construction style or size of the dwellings to be so large. The homes were made with wooden post skeletons, covered in thatch roofs, and wattle exteriors.

The largest of the houses was sixteen by nine meters (about fifteen hundred square feet), and the structures were all about five meters (sixteen feet) high. They had hearths in them, separate storage areas, and an extra tough membrane of material around the living area to keep the elements out.

The homes were also separated by fences, there were separate animal enclosures and grain threshing areas.

The excavators found over two hundred pots of all sizes, for storage and cooking. They also found evidence of dried meat and grain, plus much more. Geo-archeologist Dr. Tiziana Matarazzo says:

“The Bronze Age Campanian Plain was home to a rich diversity of food sources, including a variety of grains and barley, hazelnuts, acorns, wild apples, dogwood, pomegranates, and cornelian cherry, all extraordinarily well-preserved in the aftermath of the volcanic eruption.”

The villagers not only kept animals (pigs and goats) and farmed but also hunted. Arrowheads made from flint and bone were found, along with bones from wild boar. They may have also used animals to plow their fields.

The bones from the two skeletons were a male approximately forty to fifty years old, and a woman about twenty. It’s thought they were father and daughter.

The wear marks on the man’s teeth indicate he used them to chew on some type of material. Likely vegetable fiber for making baskets. While it appears the woman had already been through three pregnancies.

Researchers also found the bones of a six-month-old fetus placed in an urn and buried next to one of the dwellings. This appears to show ritual burial and — like today — love and care for one’s offspring.

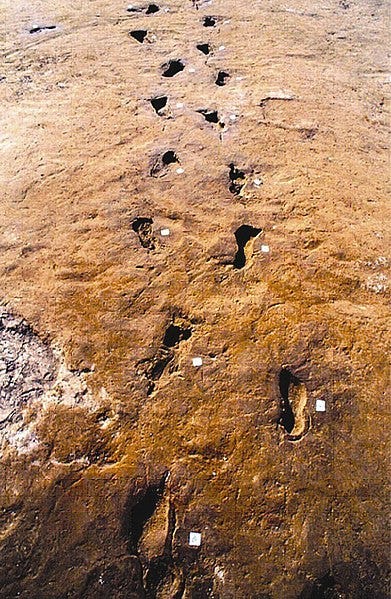

The evidence frozen in time also shows terror at the time of the eruption. Thousands of footprints extend in all directions, along with wagon wheel marks, and animal tracks. Excavations even found a clay oven in one of the dwellings with food still on it.

So, these townsfolk took off with whatever they could carry, as quickly as they could. Researchers even found animals left in their pens, and a dog hidden in a home, buried where it sought refuge.

It must have looked like the end of the world to these people accustomed to tranquil village life. But geologists refer to an event of this nature as a Plinian eruption.

Plinian Eruptions

“A cloud, from which mountain was uncertain, at this distance (but it was found afterwards to come from Mount Vesuvius), was ascending, the appearance of which I cannot give you a more exact description of than by likening it to that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches…”

— Pliny, The Younger’s description of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, 79 AD

A Plinian eruption — named after Pliny, The Younger’s description of the Pompeii event — involves a large volcanic explosion of debris and ash high into the sky. Magma builds until it hits a stress point, and then there’s an explosion like an atomic bomb, expelling hot ash and pumice stones (fragments of frothy magma).

The National Park Service explains these eruptions:

“Are extremely explosive…producing ash columns that extend many tens of miles into the stratosphere and that spread out into an umbrella shape. These large eruptions produce widespread deposits of fallout ash. Eruption columns may also collapse due to density to form thick pyroclastic flows.”

The documentary states the column of ash likely extended thirty-five kilometers (twenty miles) high and blanketed the area in total darkness. The eruption also happened in stages.

The first involved pumice fallout for about ten hours.

The second had ash falling for days, where the cloud would have extended about twenty kilometers (twelve miles) from the volcano.

In the final stage, heavy rain caused mud flows that covered and preserved the village in a mixture of mud, pumice, and ash.

It not only devastated the land, making it uninhabitable for years, but also changed the local climate. Inevitably, an actor this powerful can’t be left out of history.

The Earth As An Actor In Our History

“This eruption was so extraordinary that it changed the climate for many years afterward. The column of the Plinian eruption rose to basically the flight altitude of airplanes. It was unbelievable. The cover of ash was so deep that it left the site untouched for 4,000 years — no one even knew it was there. Now we get to learn about the people who lived there and tell their stories.”

— Dr. Tiziana Matarazzo, UConn Today

While we ultimately connect these events to people, and can’t help to be curious about the remnants of their lives buried in the ash, history reminds us of a less mortal actor called the earth. Its role also goes on indefinitely.

As Dr. Mastrolorenzo points out, Vesuvius has a cataclysmic blowout like Pompeii and Avellino every two to three thousand years. Right now, we’re about due. The volcanologist explains presently two to three million people could be at risk.

So, this story isn’t over, and history continues with an unpredictable actor working underneath our feet.

Hopefully, it’s not a repeat performance.

-Originally posted on Medium 10/2/23